Leskov is a man on the clock reduction. Online reading of the book Man on the clock Nikolai Leskov. The man on the clock. (1839). Main characters The man on the clock

Wrote the story "The Man on the Clock" Leskov. The summary will introduce the reader to this work in just a couple of minutes, the original would have taken much longer to read.

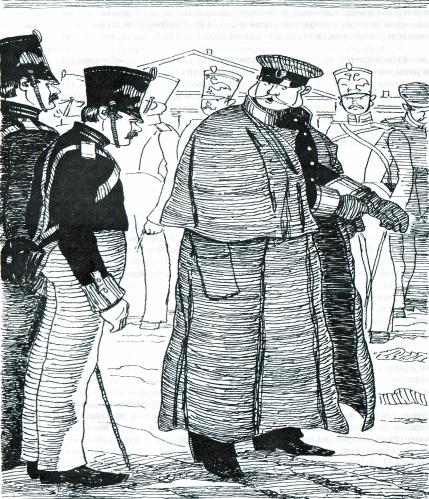

The event of the story takes place in 1839, on Epiphany days. The hero of the work is a soldier Plotnikov. He guarded the palace of Tsar Nicholas, standing at his post.

"The Man on the Clock", Leskov

A brief summary can begin with a description of a tragic incident, which ended well as a result. Postnikov stood at his post in his booth. Suddenly he heard someone asking for help. It is important to mention that the weather in those days of January was warm, so not all of it was frozen, polynyas were visible on it. It was in such an ice-hole that the man who called for help fell through. This is how Leskov's book "The Man on the Clock" begins. The soldier struggled with himself for a long time. He was a kind person. On the one hand, a sense of duty fought in him, which did not allow him to leave his post. On the other hand, the soldier was tormented by pity for a man who could drown at any time. In the end, he made up his mind and ran to help. The soldier handed the butt of the gun to the drowning man and pulled it out. Then Postnikov carried him to the shore and handed him over to an officer who was passing by.

He decided to use this case to his advantage, took the drowning man to the police department and said that it was he, the disabled officer, who saved the man. Here is an interesting content Leskov came up with. The man on the watch at this time reported the incident to his immediate superior, Miller.

Management decides what to do

The officer ordered for the time being to send the soldier who left the post to the punishment cell, and he himself contacted his boss, battalion commander Svinin, to ask what to do in this case. He arrived at the guardroom and personally interrogated Postnikov. After that, he decided to go to his boss. This is how Leskov portrays negligent bureaucratic people in his story “The Man on the Clock”. The summary will tell about the further ups and downs of the heroes in modern language. After all, in the nineteenth century they spoke a little differently, so sometimes it is difficult to read the full text of the story, it will take more time.

Unfair reward and punishment

Svinin went to General Kokoshkin, his boss. He listened to the report and ordered the bailiff of the Admiralty unit to be brought to him, where they brought the drowning and disabled officer who delivered him there. He ordered to bring to him the one who was drowning. All the trinity did not arrive soon, since there were no telephones then, and orders were delivered by a messenger. During this time, the general managed to take a nap. It can be seen that with the help of many episodes in a negative light, the bureaucracy is portrayed in his work “The Man on the Clock” by Leskov. The summary comes to the final part.

The arrivals said that it was the officer who showed miracles of nobility and saved the man. The rescued man himself did not remember exactly who helped him and confirmed that it was probably an officer.

As a result, the pseudo-savior was awarded the medal "For the salvation of the perishing." The authorities decided to punish the true hero with two hundred blows of the rod. But Plotnikov was glad that he was not put on trial.

CHAPTER FIRST

The event, the story of which is brought to the attention of readers below, is touching and terrible in its significance for the main heroic face of the play, and the denouement of the case is so original that something like it is hardly even possible anywhere except in Russia.

This is partly a courtly, partly a historical anecdote, not badly characterizing the manners and direction of a very curious, but extremely poorly marked era of the thirties of the nineteenth century.

There is no fiction in the upcoming story at all.

CHAPTER TWO

In the winter, around Epiphany, in 1839, there was a strong thaw in St. Petersburg. The weather got so wet that it was as if it were spring: the snow was melting, drops fell from the roofs during the day, and the ice on the rivers turned blue and took on water. On the Neva, in front of the Winter Palace, there were deep polynyas. The wind was blowing warm, westerly, but very strong:

water was rushing in from the seaside, and cannons were firing.

The guard in the palace was occupied by a company of the Izmailovsky regiment, commanded by a brilliantly educated and very well-placed young officer, Nikolai Ivanovich Miller (later a full general and director of the lyceum). He was a man with a so-called "humane" direction, which had long been noticed behind him and slightly harmed him in the service in the attention of higher authorities.

In fact, Miller was a serviceable and reliable officer, and the palace guard at that time did not represent anything dangerous. The time was the quietest and most serene. Nothing was required of the palace guard, except for the exact standing at their posts, and meanwhile, just here, on the guard line of Captain Miller at the palace, a very extraordinary and disturbing incident occurred, which few of the then contemporaries living out their lives now barely remember.

CHAPTER THREE

At first, everything went well in the guard: posts were distributed, people were placed, and everything was in perfect order. Sovereign Nikolai Pavlovich was healthy, went for a drive in the evening, returned home and went to bed. The palace also fell asleep. The calmest night has come. Silence in the guardhouse. Captain Miller pinned his white handkerchief to the high and always traditionally greasy morocco back of the officer's chair and sat down to pass the time with a book.

N. I. Miller was always a passionate reader, and therefore he did not get bored, but read and did not notice how the night was drifting away; but suddenly, at the end of the second hour of the night, he was alarmed by a terrible anxiety: in front of him was a non-commissioned officer for divorce, and, all pale, seized with fear, murmured quickly:

- Trouble, your honor, trouble!

- What?!

- A terrible misfortune has befallen!

N. I. Miller jumped up in indescribable anxiety and could hardly figure out what exactly the “trouble” and “terrible misfortune” consisted of.

CHAPTER FOUR

The case was as follows: a sentry, a soldier of the Izmailovsky regiment, by the name of Postnikov, standing on the clock outside at the present Jordanian entrance, heard that in the wormwood that covered the Neva in front of this place, a man was pouring and desperately praying for help.

Soldier Postnikov, from the yard of the master's people, was a very nervous and very sensitive person. For a long time he listened to the distant cries and groans of a drowning man and came to a stupor from them. In horror, he looked back and forth at all the expanse of the embankment he could see, and neither here nor on the Neva, as luck would have it, did he see a single living soul.

No one can give help to a drowning man, and he will certainly flood ...

Meanwhile, the drowning man struggles terribly long and stubbornly.

It seems to him one thing - without wasting strength, go down to the bottom, but no! His exhausted groans and invocative cries either break off and fall silent, then again begin to be heard, and, moreover, closer and closer to the palace embankment. It can be seen that the man is not yet lost and is on the right path, straight into the light of the lanterns, but only he, of course, will still not be saved, because it is here on this path that he will fall into the Jordanian hole. There he dived under the ice and the end ... Here again it subsided, and after a minute it rinsed again and groaned: "Save, save!" And now it’s so close that you can even hear splashes of water, how it rinses ...

Soldier Postnikov began to realize that it was extremely easy to save this man. If now you run away to the ice, then the sinking one will certainly be right there. Throw him a rope, or give him a six, or give him a gun, and he is saved. He is so close that he can grab his hand and jump out. But Postnikov remembers both the service and the oath; he knows that he is a sentry, and the sentry does not dare to leave his booth for anything and under no pretext.

On the other hand, Postnikov's heart is very recalcitrant; so it whines, so it knocks, so it freezes ...

At least tear it out and throw it under your own feet - it becomes so restless with him from these groans and cries ... It's scary to hear how another person is dying, and not to give this dying help when, in fact, there is a full opportunity for it , because the booth will not run away from the place and nothing else harmful will happen. "Or run away, huh?.. Will they not see?.. Oh, Lord, it would be the end! Again he is moaning..."

For one half hour, while this lasted, the soldier Postnikov was completely tormented by his heart and began to feel "doubts of reason." And he was a smart and serviceable soldier, with a clear mind, and he perfectly understood that leaving his post was such a fault on the part of the sentry, which would immediately be followed by a military court, and then a race through the ranks with gauntlets and hard labor, and maybe even "shooting"; but from the side of the swollen river the groans again float nearer and nearer, and murmuring and desperate floundering can already be heard.

- T-o-o-well! .. Save me, I'm drowning!

Here, right now, there is the Jordanian hole... The end!

Postnikov looked around once or twice in all directions. There is not a soul anywhere, only the lanterns are shaking from the wind and flickering, and along the wind, interrupted, this cry flies ... perhaps the last cry ...

Here is another splash, another monotonous cry, and the water gurgled.

The sentry could not stand it and left his post.

CHAPTER FIVE

Postnikov rushed to the gangway, fled with a beating heart onto the ice, then into the flooding water of the polynya and, soon examining where the flooded drowned man was struggling, handed him the stock of his gun.

The drowning man grabbed the butt, and Postnikov pulled him by the bayonet and pulled him ashore.

The rescued and the savior were completely wet, and as one of them, the rescued was very tired and trembling and falling, then his savior, soldier Postnikov, did not dare to leave him on the ice, but took him to the embankment and began to look around to whom he could be handed over. And meanwhile, while all this was being done, a sleigh appeared on the embankment, in which sat an officer of the then existing court invalid team (later abolished).

This gentleman, who arrived in time for Postnikov so untimely, was, presumably, a man of a very frivolous nature, and, moreover, a little stupid, and a fair amount of insolence. He jumped off the sleigh and began to ask:

- What kind of person ... what kind of people?

- He drowned, flooded, - Postnikov began.

- How did you drown? Who, you drowned? Why in such a place?

And he only spit out, and Postnikov is no longer there: he took the gun on his shoulder and again stood in the booth.

Whether or not the officer realized what was the matter, but he no longer began to investigate, but immediately picked up the rescued man in his sleigh and drove with him to Morskaya to the moving house of the Admiralty unit.

Here the officer made a statement to the bailiff that the wet man he had brought was drowning in a hole opposite the palace and was saved by him, the officer, at the risk of his own life.

The one who was rescued was now all wet, cold and exhausted. From fear and from terrible efforts, he fell into unconsciousness, and it was indifferent to him who saved him.

A sleepy police paramedic bustled around him, and in the office they wrote a protocol on the verbal statement of a disabled officer and, with the suspiciousness characteristic of police people, they were perplexed, how did he get out of the water all dry? And the officer, who had a desire to receive the established medal "for saving the perishing", explained this by a happy coincidence, but he explained it clumsily and unbelievably. Went to wake the bailiff, sent to make inquiries.

Meanwhile, in the palace, on this matter, already other, fast currents were formed.

CHAPTER SIX

In the palace guard, all the turns now mentioned after the officer took the rescued drowned man into his sleigh were unknown. There, the Izmaylovsky officer and soldiers only knew that their soldier, Postnikov, leaving the booth, rushed to save the man, and as this is a great violation of military duties, then Private Postnikov will now certainly go to trial and be beaten, and all commanding officials, starting from company to the commander of the regiment, terrible troubles will go to which nothing can be objected to or justified.

The wet and trembling soldier Postnikov, of course, was immediately relieved of his post and, being brought to the guards, frankly told N.I. drowned man and ordered his coachman to gallop to the Admiralty part.

The danger became more and more inevitable. Of course, the disabled officer will tell the bailiff everything, and the bailiff will immediately bring this to the attention of the chief police chief Kokoshkin, and he will report to the sovereign in the morning, and the "fever" will go.

There was no time to argue for a long time, it was necessary to call the elders to the cause.

Nikolai Ivanovich Miller immediately sent an alarming note to his battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Svinin, in which he asked him to come to the palace guardhouse as soon as possible and by all means help the terrible misfortune that had occurred.

It was already about three o'clock, and Kokoshkin appeared with a report to the sovereign quite early in the morning, so that there was very little time left for all thoughts and all actions.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Lieutenant Colonel Svinin did not have that compassion and that kindness that always distinguished Nikolai Ivanovich Miller; Svinin was not a heartless man, but first of all and most of all a "serviceman" (a type that I now again recall with regret). Svinin was strict and even liked to flaunt his exacting discipline. He had no taste for evil and did not seek to inflict unnecessary suffering on anyone; but if a person violated any duty of service, then Svinin was inexorable. He considered it inappropriate to enter into a discussion of the motives that guided the movement of the guilty in this case, but kept to the rule that in the service all guilt is to blame. And therefore, in the guard company, everyone knew that ordinary Postnikov would have to endure for leaving his post, then he would endure, and Svinin would not grieve about this.

That is how this staff officer was known to his superiors and comrades, among whom there were people who did not sympathize with Svinin, because at that time "humanism" and other similar delusions had not yet fully emerged. Svinin was indifferent to whether the "humanists" condemned or praised him. Asking and pleading with Svinin, or even trying to pity him, was a completely useless thing. From all this, he was tempered by the strong temper of the career people of that time, but he, like Achilles, had a weak spot.

Svinin also had a well-begun service career, which he, of course, carefully guarded and cherished so that not a single speck of dust sat on it, as on a ceremonial uniform; meanwhile, the unfortunate trick of a man from the battalion entrusted to him was bound to cast a bad shadow on the discipline of his entire unit. Whether the battalion commander is guilty or not guilty of what one of his soldiers did under the influence of passion for the noblest compassion - this will not be analyzed by those on whom Svinin's well-begun and carefully maintained service career depends, and many will even willingly roll a log under his feet, to give way to your neighbor or to move a young man who is being patronized by people in case. The sovereign, of course, will be angry and will certainly tell the regimental commander that he has “weak officers”, that their “people are loose”. And who did it? - Pig. This is how it will be repeated that "Svinyin is weak", and so, perhaps, the shame of weakness will remain an indelible stain on his, Svinyin's, reputation. Then he would not be anything remarkable among his contemporaries and not leave his portrait in the gallery of historical figures of the Russian state.

At that time, although they did little to study history, they nevertheless believed in it, and especially willingly strove to participate in its composition.

CHAPTER EIGHT

As soon as Svinin received an alarming note from Captain Miller at about three o'clock in the morning, he immediately jumped out of bed, dressed in uniform and, under the influence of fear and anger, arrived at the guardhouse of the Winter Palace. Here he immediately interrogated Private Postnikov and became convinced that an incredible event had taken place. Private Postnikov again quite frankly confirmed to his battalion commander everything that had happened on his watch and that he, Postnikov, had previously shown to his company captain Miller. The soldier said that he was "to blame to God and the sovereign without mercy", that he stood on the clock and, hearing the groans of a man drowning in a hole, suffered for a long time, was in a struggle between duty and compassion for a long time, and, finally, temptation attacked him , and he could not stand this struggle: he left the booth, jumped onto the ice and pulled the drowning man ashore, and here, as a sin, he was caught by a passing officer of the palace disabled team.

Lieutenant Colonel Svinin was in despair; he gave himself the only possible satisfaction by taking out his anger on Postnikov, whom he immediately sent right from here under arrest to a barracks punishment cell, and then said a few barbs to Miller, reproaching him with "humanitarianism", which is not suitable for anything in military service; but all this was not enough to improve the matter. It was impossible to find, if not an excuse, then an apology for such an act as leaving his post as sentry, and there was only one way out - to hide the whole matter from the sovereign ...

But is it possible to hide such an incident?

Apparently, this seemed impossible, since not only all the guards knew about the salvation of the deceased, but that hated invalid officer who, of course, still managed to bring all this to the knowledge of General Kokoshkin, also knew.

Where to jump now? To whom to rush? From whom to seek help and protection?

Svinin wanted to gallop to Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich and tell him everything frankly. Such maneuvers were then in use. Let the Grand Duke, according to his ardent character, get angry and scream, but his temper and custom were such that the stronger he was harsh at first and even seriously offended, the sooner he would have mercy and intercede himself. There were many such cases, and they were sometimes deliberately searched for. "The scolding did not hang at the gate," and Svinin would very much like to reduce the matter to this favorable situation, but is it really possible to enter the palace at night and disturb the Grand Duke? And it will be too late to wait for the morning and report to Mikhail Pavlovich after Kokoshkin has visited the sovereign with a report. And while Svinin was agitated in the midst of such difficulties, he became limp, and his mind began to see another way out, which until now had been hidden in the fog.

CHAPTER NINE

Among the well-known military methods, there is one such that, at the moment of the highest danger threatening from the walls of a besieged fortress, one does not move away from it, but directly goes under its walls. Svinin made up his mind not to do anything that had occurred to him at first, but to immediately go straight to Kokoshkin.

A lot of terrifying and absurd things were said about Chief Police Master Kokoshkin in St. Petersburg at that time, but, among other things, they asserted that he possessed an amazing many-sided tact and, with the assistance of this tact, not only “knows how to make an elephant out of a fly, but just as easily knows how to make a fly out of an elephant.” ".

Kokoshkin was indeed very stern and very formidable and instilled great fear in everyone, but he sometimes pacified the rascals and good merry fellows from the military, and there were many such rascals then, and more than once they happened to find themselves in his person a powerful and zealous defender . In general, he could do a lot and knew how to do a lot, if he only wanted to. This is how Svinin and Captain Miller knew him. Miller also strengthened his battalion commander to dare to go immediately to Kokoshkin and trust his generosity and his "multilateral tact", which will probably dictate to the general how to get out of this unfortunate case so as not to infuriate the sovereign, which Kokoshkin , to his credit, always avoided with great diligence.

Svinin put on his greatcoat, fixed his eyes upward, and exclaiming several times: "Lord, Lord!" - went to Kokoshkin.

It was already early five o'clock in the morning.

CHAPTER TEN

The chief police chief Kokoshkin was awakened and reported to him about Svinin, who had arrived on an important and urgent matter.

The general immediately got up and went out to Svinin in an arkhaluchka, rubbing his forehead, yawning and shivering. Everything that Svinin told, Kokoshkin listened to with great attention, but calmly. During all these explanations and requests for indulgence, he said only one thing:

- The soldier abandoned the booth and saved the man?

- Exactly so, - answered Svinin.

- And the booth?

- Remained at this time empty.

- Hm... I knew that it remained empty. I'm glad it didn't get stolen.

From this, Svinin was even more convinced that he already knew everything and that he, of course, had already decided for himself in what form he would present this at the morning report to the sovereign, and would not change his decision. Otherwise, such an event as the sentries leaving their post in the palace guard, no doubt, should have alarmed the energetic Chief Police Master much more.

But Kokoshkin knew nothing. The bailiff, to whom the disabled officer appeared with the rescued drowned man, did not see any particular importance in this matter. In his eyes, it was not at all such a thing as to disturb the tired chief police chief at night, and, moreover, the event itself seemed rather suspicious to the bailiff, because the invalid officer was completely dry, which could not be if he was rescuing a drowned man with danger to own life. The bailiff saw in this officer only an ambitious and a liar who wanted to have one new medal on his chest, and therefore, while his duty officer was writing the protocol, the bailiff kept the officer in his place and tried to extort the truth from him by questioning small details.

The bailiff was also not pleased that such an incident happened in his unit and that the drowning man was pulled out not by a policeman, but by a palace officer.

Kokoshkin’s calmness was explained simply, firstly, by the terrible fatigue that he experienced at that time after all-day fuss and nightly participation in extinguishing two fires, and secondly, by the fact that the work done by sentry Postnikov, his, Mr. Ober - the police chief, did not directly concern.

However, Kokoshkin immediately made a corresponding order.

He sent for the bailiff of the Admiralty unit and ordered him to immediately appear along with the disabled officer and the rescued drowned man, and Svinin asked to wait in a small waiting room in front of the office. Then Kokoshkin retired to his study and, without closing the door behind him, sat down at the table and began to sign papers; but immediately bowed his head in his hands and fell asleep at the table in an armchair.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

At one o'clock in the afternoon, the disabled officer was indeed again demanded to Kokoshkin, who very affectionately announced to him that the sovereign was very pleased that among the officers of the disabled team of his palace there were such vigilant and selfless people, and he was granted him a medal "for saving the dead." At the same time, Kokoshkin personally handed the hero a medal, and he went to flaunt it. The matter, therefore, could be considered completely done, but Lieutenant Colonel Svinin felt some kind of incompleteness in it, and considered himself called upon to put a point sur les i 1.

1 Dot over i (French)

He was so alarmed that he fell ill for three days, and on the fourth he got up, went to Petrovsky's house, served a thanksgiving service before the icon of the Savior, and, returning home with a calm soul, sent Captain Miller to ask for him.

“Well, thank God, Nikolai Ivanovich,” he said to Miller, “now the storm that weighed on us has completely passed, and our unfortunate business with the sentry has been completely settled. Now it seems we can breathe easy. We owe all this, no doubt, first to the mercy of God, and then to General Kokoshkin. Let it be said of him that he is both unkind and heartless, but I am filled with gratitude for his generosity and respect for his resourcefulness and tact. He surprisingly skillfully took advantage of the boasting of this disabled swindler, who, in truth, should not have been awarded a medal for his impudence, but torn on both crusts in the stable, but there was nothing else to do: they had to be used to save many, and Kokoshkin turned the whole thing around. so cleverly that no one got the slightest trouble - on the contrary, everyone is very happy and satisfied. Between us, to say, I was told through a reliable person that Kokoshkin himself is very pleased with me. He was pleased that I did not go anywhere, but came directly to him and did not argue with this rogue who received the medal. In a word, no one was hurt, and everything was done with such tact that there is nothing to fear in the future, but we have a small flaw. We, too, must tactfully follow the example of Kokoshkin and finish the matter on our part in such a way as to protect ourselves later, just in case. There is one more person whose position has not been formalized. I'm talking about Private Postnikov. He is still in the punishment cell under arrest, and he, no doubt, is tormented by the expectation of what will happen to him. It is necessary to stop his painful languor.

- Yes, it's time! - prompted the delighted Miller.

- Well, of course, and you better do it all:

please go immediately to the barracks, gather your company, get Private Postnikov out of custody and punish him before the formation with two hundred rods.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Miller was amazed and made an attempt to persuade Svinin to completely spare and forgive ordinary Postnikov, who, without that, had already suffered a lot, waiting in the punishment cell for a decision on what would happen to him; but Svinin flared up and did not even let Miller continue.

“No,” he interrupted, “leave that alone: I just told you about tact, and you are immediately beginning to be tactless!” Leave it!

Svinyin changed his tone to a more dry and formal one, and added with firmness:

- And how in this matter you yourself are also not entirely right and even very guilty, because you have a softness that does not suit a military man, and this lack of your character is reflected in the subordination in your subordinates, then I order you to personally attend the execution and insist so that the section is made seriously, as strictly as possible. For this, if you please, order that young soldiers from the newly arrived from the army be whipped with rods, because our old people are all infected on this score with Guards liberalism; they do not flog a comrade as they should, but only scare fleas behind his back. I'll come by myself and see for myself how the guilty person will be done.

Evasion from any official orders of the commanding person, of course, did not take place, and the soft-hearted N.I. Miller had to exactly fulfill the order he received from his battalion commander.

The company was lined up in the courtyard of the Izmaylovsky barracks, rods were brought from the reserve in sufficient quantities, and Private Postnikov, taken out of the punishment cell, "was made" with the diligent assistance of young comrades who had just arrived from the army. These people, unspoiled by the liberalism of the guards, perfectly set out on him all the points sur les i, fully determined for him by his battalion commander. Then the punished Postnikov was raised and directly from here on the same greatcoat on which he was flogged, transferred to the regimental infirmary.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

The battalion commander Svinin, upon receiving a report on the execution of the execution, immediately himself paternally visited Postnikov in the infirmary and, to his pleasure, was most clearly convinced that his order had been executed to perfection. Compassionate and nervous Postnikov was "done properly". Svinin was satisfied and ordered to give the punished Postnikov a pound of sugar and a quarter of a pound of tea from himself, so that he could enjoy himself while Postnikov was on the mend, lying on his bed, he heard this order about tea and answered.

- Much pleased, your highness, thank you for your fatherly mercy.

And he really was "satisfied", because, sitting for three days in a punishment cell, he expected much worse. Two hundred rods, according to the strong time of that time, meant very little in comparison with the punishments that people endured according to the sentences of a military court; and this is precisely the punishment that Postnikov would have received if, fortunately for him, all those bold and tactical evolutions, which are described above, did not take place.

But the number of all those who were satisfied with the reported incident was not limited to this.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Under the mute feat of ordinary Postnikov spread through various circles of the capital, which at that time lived in an atmosphere of endless gossip in printed voicelessness. In oral transmissions, the name of the real hero - the soldier Postnikov was lost, but the epic itself swelled up and took on a very interesting, romantic character.

It was said that some unusual swimmer was sailing towards the palace from the side of the Peter and Paul Fortress, at whom one of the sentries standing at the palace shot and wounded the swimmer, and a passing invalid officer rushed into the water and saved her, for which they received: one - due reward, and the other is a well-deserved punishment. This absurd rumor also reached the courtyard, where at that time the Vladyka, cautious and not indifferent to "secular events", favorably favored the pious Moscow family of the Svinins.

The perceptive lord seemed obscure to the story of the shot. What is a night swimmer? If he was a runaway prisoner, then why was the sentry punished, who fulfilled his duty by shooting him when he sailed across the Neva from the fortress? If this is not a prisoner, but another mysterious person who had to be rescued from the waves of the Neva, then why could the sentry know about him? And then again it cannot be that it is so, as the world talks about it. In the world, many things are taken extremely lightly and "talk about", but those who live in monasteries and in farmsteads take everything much more seriously and know the real thing about secular affairs.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Once, when Svinin happened to be at the lord's to receive a blessing from him, the highly esteemed host spoke to him "by the way, about the shot." Svinin told the whole truth, in which, as we know, there was nothing like what was told about "by the way, about the shot."

Vladyko listened to the real story in silence, slightly moving his little white rosary and not taking his eyes off the narrator. When Svinin had finished, Vladyka said in a soft, murmuring speech:

- Therefore, it must be concluded that in this case, not everything and not everywhere was stated in accordance with the full truth?

Svinin hesitated and then answered with a bias that it was not he who reported, but General Kokoshkin.

In silence, Vladyko passed the rosary several times through his wax fingers and then said:

- One must distinguish between what is a lie and what is an incomplete truth.

Again the rosary, again silence, and finally low-pitched speech.

- Incomplete truth is not a lie. But about this least.

- This is really so, - the encouraged Svinin spoke up - Of course, what bothers me most of all is that I had to punish this soldier, who, although he violated his duty ...

Rosary and low-pitched interruption:

- Duty of service must never be violated.

Yes, but he did it out of generosity, out of compassion, and, moreover, with such a struggle and danger: he understood that in saving the life of another person, he was destroying himself. This is a high, holy feeling!

- The holy is known to God, but punishment on the body of a commoner is not destructive and does not contradict either the custom of the peoples or the spirit of Scripture. The vine is much easier to bear on the gross body than subtle suffering in the spirit. In this, justice has not suffered from you in the least.

- But he is also deprived of the reward for saving the perished.

- The salvation of the perishing is not a merit, but rather a duty. Whoever could save and did not save is subject to the punishment of laws, and whoever saved, he fulfilled his duty.

Pause, rosary and quiet jet:

- It can be much more useful for a warrior to endure humiliation and wounds for his feat than to be extolled by a sign. But what is most important in all this is to be careful about this whole matter and not to mention anywhere about who, on any occasion, was told about this.

Obviously, Vladyka was also pleased.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

If I had the boldness of the happy chosen ones of heaven, to whom, according to their great faith, it was given to penetrate the secrets of God's gaze, then I, perhaps, would have dared to allow myself the assumption that, probably, God himself was pleased with the behavior of Postnikov's meek soul created by him. But my faith is small; it does not give my mind the strength to see so high: I hold on to earthly and dusty things. I'm thinking of those mortals who love goodness just for the very good, and don't expect any reward for it anywhere. These direct and reliable people, too, it seems to me, should be completely satisfied with the holy impulse of love and the no less holy patience of the humble hero of my precise and artless story.

- Text for the reader's diary

- The main idea of the story

- Summary

- Summary by chapter

Very briefly

Year: 1887 Genre: story

Main characters: soldier Postnikov, head of the battalion Svinin and drowning

Soldier Postnikov was standing guard when he heard a call for help. He kept thinking and pondering whether he should leave his post and see who was in trouble, or in any case should he remain in the service? Postnikov saves a man drowning in the river and immediately returns. The victim is taken away by a disabled officer. Postnikov was punished for his absence during the service. He is sent to the punishment cell.

A lot of high-ranking officials were involved in history so that it would not become known to the sovereign. The police chief, after interrogating the disabled officer and the rescued one, decides to reward the officer. He receives a medal for a good deed. A completely different fate awaits the poor soldier. They pulled him out of the punishment cell, but he received two hundred lashes. For the soldier, this punishment was not very terrible, since he was waiting for the worst decision. The priest learns about the whole truth. He concludes that lashing was a better solution for the soldier than his exaltation and praise.

The main idea. Human moral duty is always above all else, even if a person himself may suffer because of the right deed.

The action begins with a description of warm weather in the middle of winter. At Epiphany in 1839, the weather was strangely warm. It was so warm that the ice on the Neva began to melt. One soldier, who that day was a sentry in the Izmailovsky regiment, heard strange human screams and cries. Someone called for help. The soldier's name was Postnikov. He did not know what to do, because he could not leave his place of guard, and the man kept calling for help. He decided to run to see what was going on. The voice came from the river. Postnikov saved a drowning man by pulling him out with a gun. The life of the poor man was still in danger, because he was very cold and completely weak. At that moment the soldier saw an officer in a wheelchair. He immediately returned to the guard. The officer picked up the drowning man and, imagining himself a savior, took him to a moving house.

Several minutes of Postnikov's absence did not remain secret. His absence was noticed and sent immediately to Officer Miller. Postnikov was put in a punishment cell. Because of the fear that the sovereign might find out about everything, the commander was forced to turn to officer Svinin for help. It got to the point where a lot of people were involved. After turning to Svinin, it was decided to ask the chief police chief Kokoshkin for advice. The latter decided to take a decisive step.

First of all, he considered it necessary to meet with the disabled officer himself and with the man whose rescue had caused such a stir among numerous dignitaries. The disabled officer and the drowning man were thoroughly interrogated. As a result of this interrogation, the chief of police became aware that, apart from the sentry, no one else had an idea about what had happened, and that he was the only witness to the whole story of salvation. The disabled officer again acted as a savior. This time his feat was appreciated as it should be. He was awarded a medal designed for similar stories, when one saves the life of another person.

The real savior was in the punishment cell all this time. He had already managed to change his mind in his thoughts and try to predict any course of events. His reward for saving a poor dying man was a punishment, namely, to receive two hundred lashes with a rod. After his punishment, the soldier was nevertheless very pleased with Svinin's decision, since much more serious rewards came to his mind than the blows he received with a rod. The priest became aware of this story. He thought about what had happened and concluded that it was better to punish a soldier for such a feat than to exalt him. So there will be more benefits.

Summary The man on the clock chapter by chapter (Leskov)

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

This touching story happened in the winter in St. Petersburg. On guard in the palace was a company commanded by officer Nikolai Miller. He was a very reliable and humane person.

Chapter 3

The night was quiet and calm, Officer Miller whiled away the time reading a book. Suddenly, they report to him that something bad has happened.

Chapter 4

It turned out that sentry Postnikov, who was on guard, heard a cry for help from a drowning man. Being a very sensitive person, he left his post and went to the aid of a drowning man.

Chapter 5

Soldier Postnikov rushed to the ice and pulled the man out of the water. At that moment, a sleigh pulled up to them. In them sat a frivolous and impudent officer. He took the rescued man and took him to the police. At the station, wanting to receive a reward, he said that he had saved a drowning man.

Chapter 6

Soldier Postnikov reports to Miller about what happened. Miller understands that all commanding persons are in danger, and the soldier cannot avoid serious punishment. He sends a note about the incident to his commander Svinin.

Chapter 7

Lieutenant Colonel Svinin valued his place in the service very much. He did not tolerate violations of service and was in this regard a strict and inexorable person.

Chapter 8

As soon as the lieutenant colonel read the note from Miller, he immediately went to interrogate the soldier Postnikov. After the interrogation, being in a state of anger and despair, he sent the soldier under arrest to the punishment cell. Then Svinin began to think about how to hide what had happened from the king.

Chapter 9

Lieutenant Colonel Svinin decides to go to General Kokoshkin. He knows that this person will help to get out of any situation so as not to anger the king.

Chapter 10

Kokoshkin listens to Svinin's story and calls the bailiff, who received the rescued man at night, and the officer who supposedly saved the man.

Chapter 11

They come to Kokoshkin together with the rescued person. Kokoshkin conducts a conversation with the saved. He understands that he does not remember the face of the man who saved him. Kokoshkin assures the rescued that the officer who brought him to the station is his savior.

Chapter 12

Kokoshkin promises to present an award to the officer who supposedly saved the man. Thus, he wants to get out of the current unpleasant situation. He understands that now no one will know that the soldier left the post and saved the man.

Chapter 13

Kokoshkin presents the medal to the liar. Svinin feels relieved, he orders Miller to release the soldier Postnikov and punish him with rods in front of the soldiers.

Chapter 14

Miller asks to spare the soldier, but the lieutenant colonel demands to follow the order. Postnikov is released, whipped and sent for treatment.

Chapter 15

Svinin visits a soldier in the infirmary and orders him to give him sugar and tea. The soldier thanks him for the treats. He was pleased with this outcome of events, as he was counting on a worse punishment.

Chapter 16

Rumors and fictitious tales about the feat of the soldier Postnikov begin to spread around the capital. The St. Petersburg Bishop, to whom these stories have also reached, wants to find out how everything really happened.

Chapter 17

Somehow, Vladyka meets with Svinin and learns the whole truth about the incident. Svinin complains that his conscience torments him because another person received the award, and the soldier was punished with rods. Vladyka assures him that he did everything right.

Chapter 18

Picture or drawing Man on the clock

Other retellings and reviews for the reader's diary

- Summary of The Hobbit, or Tolkien's There and Back Again

Gandalf comes to Bilbo with the dwarves. They take the Hobbit with them on their journey. They need to take the treasure from the dragon Smaug.

Article menu:

The text we are interested in belongs to Nikolai Leskov, an author whose works often touch on moral issues. "The man on the clock" is just a confirmation of this rule. What is the text about - in a nutshell? Leskov writes, of course, about human duty. In fact, the reader is faced with the dilemma faced by the protagonist. The sentry sees a man drowning in a cold river. However, can a sentry leave his post? No. But the duty of man, meanwhile, requires that the hero break his duty as a sentry and save the poor man from drowning. What will our hero choose? You will learn about this from the summary of the story. In the meantime, we would like to dwell - briefly - on the history of the writing of this text.

The history of the creation of the work

Leskov's text was published in the spring of 1887. A story was published in Russian Thought, and was then called "The Salvation of the Perishing". Only after some time the author gave his creation the name by which the text is known today. The plot is based on an absolutely real story, and the characters sometimes bear the features of persons who also existed in reality - usually these are officials, civil servants under Tsar Nikolai Pavlovich.

Artistic Features of "The Man on the Clock"

The composition of Leskov's work can be called linear, because the events here develop diachronically. First, the reader is faced with the moral choice of the protagonist, who experiences a sudden problem very emotionally. After that, the writer talks about the actions of officials - bosses. In these moments one can hear irony, sarcasm and bitterness, because morality is so often obscured by careerist motives, desire to curry favor. And the life of a person in such a paradigm turns into something devalued.

The idea of the work Man on the clock

So what does the author of this work want to convey to the reader? First of all, Leskov writes about the absurdity and inhumanity of a system that focuses on fears, on demonstrativeness - empty and meaningless. In such circumstances, "human, too human", as the German philosopher Nietzsche might have said, recedes somewhere into the background, and even into the third plan. And the place of the “protagonist”, the main star on the stage, is occupied by formality and window dressing.

The philosophical essence of the text is close to the idea of the work. Leskov, in fact, depicts the thorny and difficult path of knowing one's own destiny - here on earth. Here, it would seem, is an obvious situation: the main character is given a choice - the life of a person or the duty of a sentry. Man's work responsibilities, of course, are much lower than those responsibilities in relation to the central value of society - life. However, unfortunately, the values in our society have long been confused and mixed up, so not everyone approves of Postnikov's choice. As a result, the situation does begin to resemble absurdity.

Theme "Man on the clock"

As is often the case, the idea of the text echoes the theme, but the theme is not identical with the idea. The theme of the work concerns conscience, and also shows the reader what humanity is, opposing the soullessness of formalism. The qualities of humanity are embodied in the main character - Postnikov. The man is an example of Christian values, and even the character's last name seems to hint at this. Sacrifice, lack of ambition, desire to curry favor, simplicity - all this is characteristic of Postnikov's personality. This hero is opposed by Svinin, whose surname is also, as they say, "speaking". This is the embodiment of that same formalism, negative qualities, such as careerism, dependence on the opinions of superior people.

Key themes of the work

So, the first theme that catches your eye is, of course, the motive of love for your neighbor, the motive of sympathy and compassion for people. Against the background of this theme, the features of the dominant order are revealed, the arbitrariness and lawlessness that reigns among the protagonist's entourage is revealed. Performing a feat, you never know what will follow this act: either a reward, or a punishment, and sometimes even death may follow. The story also has notes of religiosity, there is a reference to Christianity and the values of this religion: these are, for example, righteousness, nobility, philanthropy (humanism and humanity), kindness, peace of mind, conscientiousness, etc. At the same time, the author also shows that indifference and indifference to man reigns in society.

Central problems of the text

Along with the themes, the writer also turns to the disclosure of certain problems that are relevant not only for that time, but also for ours.

Firstly, in the work the problem of humanism and duty sounds - as components of military service, the life of a soldier. There is a natural conflict between military duty and human duty. The writer demonstrates how difficult it is sometimes to choose between two opposing principles.

Secondly, the text focuses on the relationship between soldiers and superiors, officers, and shows the self-will of those who are higher on the hierarchy ladder. Warriors of lesser rank are often obliged to blindly follow the orders of senior commanders and comrades.

Thirdly, "The Man on the Clock" reflects - like a mirror - the problem of meanness, which is associated with self-interest, painful ambition and the desire to curry favor and thus win a warmer place for oneself. Some people on the way to the goal show themselves generous, but others - and most of these people - are cowardly, show hypocrisy, self-interest, a tendency to opportunism.

Fourthly, the problem of lies comes to the fore in Leskov's text. People often lie, and sometimes they do not tell the whole truth, which also equates to a lie. And, finally, the last obvious problem concerns human weaknesses: for example, addiction to bad habits, alcohol. Weaknesses of this kind often lead to tragedies, so the person whom the protagonist saves also ended up in ice water because of such a passion for drinking.

Separately, there is the problem of valor. In Russian culture - and at this point the author especially focuses attention - feats have always been honored. This tradition began with the feats of arms of heroes. This is not just a manifestation of physical strength, but also a demonstration of spiritual strength. Now the world seems to be turned upside down, and valor has lost its original meaning. Leskov shows himself to be a connoisseur of the human soul, and the story itself is an example of a masterful psychological analysis. The author reveals the inner conflict that one day is brewing in the soul of every person. But for courageous deeds, an unfair reward follows, and the dignity of a warrior and a brave man is humiliated and trampled on. What is the position of the author himself? Leskov very ironically writes that he does not know how God himself evaluates the act of the hero - Postnikov, there, in heaven. Even if Postnikov does not go to heaven, and does not receive a well-deserved (as it seems) reward for his act, the man’s soul is still calm and peaceful, because Postnikov followed his conscience. Be that as it may, the author writes, there will always be people in this world who do bold deeds not for the sake of awards or promotion.

Main characters The man on the clock

So, before a direct chronological presentation of events, let us turn - briefly - to the characteristics of the characters in this work.

Postnikov's image

The protagonist of the work is represented by a soldier who serves in the Izmailovsky regiment. Despite the fact that Postnikov is a military man, a sentinel, the nature of a young man - like that of the Japanese poet Ryunosuke Akutagawa - is nervous, sensitive, and does not fit into the world around him at all. A military man must be guided by a charter, an order, but for Postnik the main thing is still the command of the heart, conscience, the order of the soul. This is an example of humanism, a compassionate attitude towards people. For the noble cause, the hero was "awarded" with two hundred lashes, but Postnikov would not have done otherwise if he had managed to turn back time and change his mind.

The image of Nikolai Ivanovich Miller

The captain is the embodiment of a subtle, educated and friendly nature towards people. This is a noble and well-mannered officer who appreciates good literature. Responsibility for those who are subordinate to him, softness of soul, the ability to show pity - these are the characteristic features of the personality of this hero. At the same time, such positive characteristics make the surrounding officers hate Miller and condemn the hero. The hero is a perfectionist, a pedantic and accurate performer of his duty.

The image of Svinin

The lieutenant colonel is the negative character of this work. Svinin can be dubbed a "serviceman", who believes that the motives of the soldiers are the twenty-fifth matter. The main thing is the charter, the order. If you violated the charter - no matter for what reasons - then bear the punishment. And, as a rule, Svinyin chose the most severe punishments. The lieutenant colonel does not know pity and compassion, he values only his own reputation and service prospects. Svinin is ready for any subservience, if only to place his person in a number of historical figures in Russia. No, it cannot be said that Svinin is a completely soulless man, it’s just that this hero is overly strict, and work, time, maybe mental trauma, made Svinin callous. This also, of course, testifies to the weakness of nature.

The image of Kokoshkin

The writer presents the chief police chief as a surprisingly tactful person. At the same time, Kokoshkin has the ability to "make an elephant out of a fly." On the one hand (according to the environment), this is a demanding, strict boss. However, on the other hand, Kokoshkin sometimes manifests himself as a gentle, diligent, and patronizing friend. The hero is able to protect a friend and neighbor. A man is characterized by excessive workaholism, often to the detriment of health. Abilities and will for Kokoshkin are the key to achieving unprecedented heights.

Chapter first

This story could only happen in Russia, since stories with such unusual and sometimes absurd endings usually happen only here. The story told resembles a joke, but there is no fiction in it at all.

Chapter Two

In 1839 the winter was warm. In the area of baptism, drops were already ringing with might and main, and it seemed that spring had come.

At that time, the Izmailovsky regiment, commanded by Nikolai Ivanovich Miller, kept guard in the palace - he was a reliable man, albeit humane in his views.

Chapter Three

In the guard, everything was calm - the sovereign was not sick, and the guards regularly performed their duties.

Miller never got bored on guard - he loved to read books and spent the whole night reading.

One day, a frightened sentry ran up to him and said that something bad had happened.

Chapter Four

Soldier Postnikov, who at that time was on guard for about an hour, heard the screams of a drowning man. At first, he was afraid for a long time to leave his post, but then he nevertheless decided and pulled out the drowning man.

Chapter Five

Postnikov led the drowning man to the embankment and hastily returned to his post.

Another officer took advantage of this opportunity - he attributed the salvation of the drowning man to himself, since for this he should have been awarded a medal.

Chapter six

Postnikov confessed everything to Miller.

Miller reasoned as follows: since a disabled officer drove a drowning man to the Admiralty part on his sleigh, it means that everyone will quickly become aware of the incident.

Miller began to act quickly - he informed Lieutenant Colonel Svinin about what had happened.

Chapter Seven

Svinyin was a very demanding person in terms of discipline and disciplinary violations.

He was not distinguished by humanity, but he was not a despot either. Svinyin always acted according to the charter, as he wanted to reach heights in his career.

Chapter Eight

Svinin arrived and interviewed Postnikov. Then he reproached Miller for his humanity, sent Postnikov to a punishment cell and began to look for a way out of this situation.

Chapter Nine

At five in the morning, Svinin decided to go personally to the chief of police Kokoshkin and consult with him.

Chapter Ten

Kokoshkin was still asleep at that time. The servant woke him up. After listening to Svinin, Kokoshkin sent for a disabled officer, a drowned man, and for a bailiff of the Admiralty unit.

Chapter Eleven

When everyone gathered, the drowning man said that he wanted to shorten the path, but lost his way and fell into the water, it was dark and he did not consider his savior, most likely it was a disabled officer. Svinin was amazed by the story.

Chapter Twelve

The disabled officer confirmed the story. Kokoshkin had another talk with Svinin and sent him on his way.

Chapter Thirteen

Svinin told Miller that Kokoshkin had managed to settle everything and now it was time to release Postnikov from the punishment cell and punish him with rods.

Chapter Fourteen

Miller tried to convince Svin'in not to punish Postnikov, but Svin'in did not agree. When the company was built, Postnikov was taken out and flogged with rods.

Chapter fifteen

Svinin then personally visited Postnikov in the infirmary to make sure that the punishment was carried out in good faith.

Chapter Sixteen

The story about Postnikov began to spread quickly, then gossip about the disabled officer joined him.

We suggest that you familiarize yourself with which Nikolai Leskov wrote.

The result is a fantastic story.

Chapter Seventeen

One day Svinin was at Vladyka's and he asked him about the rumors around this unusual story - Svinin told everything as it was.

Dear readers! We offer you to get acquainted with the author of which Nikolay Leskov.

The sovereign was pleased with the decision that Svinin made in relation to Postnikov.

Chapter Eighteen

Winter in St. Petersburg in 1839 was with strong thaws. Sentry Postnikov, a soldier of the Izmailovsky regiment, stood at his post. He heard that a man had fallen into the hole and was crying for help. The soldier did not dare to leave his post for a long time, because this was a terrible violation of the Charter and almost a crime. The soldier suffered for a long time, but in the end he made up his mind and pulled out the drowning man. Just then a sleigh was passing by, in which an officer was sitting. The officer began to understand, and in the meantime Postnikov quickly returned to his post. The officer, realizing what had happened, delivered the rescued man to the guardhouse. The officer reported that he had saved a drowning man. The rescued person could not say anything, because he lost his memory from what he had experienced, and he did not really understand who saved him. The case was reported to Lieutenant Colonel Svinin, a diligent campaigner.

Svinin considered himself obliged to report to Chief Police Officer Kokoshkin. The case received wide publicity.

The officer who pretended to be a rescuer was awarded a medal "for saving the dead." Private Postnikov was ordered to be whipped before the formation with two hundred rods. The punished Postnikov was transferred to the regimental infirmary in the same overcoat on which he was flogged. Lieutenant Colonel Svinin ordered the punished man to be given a pound of sugar and a quarter of a pound of tea.

Postnikov replied: "I am very pleased, thank you for the father's mercy." In fact, he was pleased, sitting for three days in a punishment cell, he expected much worse that a military court could award him.

Summary of Leskov's story "The Man on the Clock"

Other essays on the topic:

- This author hears the story from the nanny of his younger brother, Lyubov Onisimovna, in the past, the beautiful actress of the Oryol theater, Count Kamensky. On the...

- Childhood and youth of Alexander Ryzhov In the reign of Catherine II, in the town of Soligalich, Kostroma province, in the family of a small clerical servant Ryzhov ...

- A new senior officer, Baron von der Behring, arrives on the corvette in the Singapore roadstead. The ship is on a circumnavigation already...

- Sherlock Holmes is approached for help by a young man, Mr. Bennet, who is an assistant to the famous Professor Presbury and the fiancé of his only daughter ....

- Chapter One Traveling on Lake Ladoga on a steamboat, travelers, among whom was the narrator, visited the village of Korela. As the journey continues...

- A few years ago, an old landowner lent 15,000 rubles to a St. Petersburg dandy on the security of the estate. The old woman knew the mother of this dandy and completely ...

- The lace-maker Domna Platonovna, known to the narrator, "has the most immense and diverse acquaintance" and is sure that she owes this to her simplicity and...

- Two young girls, "poplar and birch", Lizaveta Grigorievna Bakhareva and Evgenia Petrovna Glovatskaya are returning from Moscow after graduation. By...

- In the inn, several travelers take refuge from the weather. One of them claims that "every saved person ... an angel guides", and he ...

- "Russian man on rendez-vous" refers to journalism and has the subtitle "Reflections after reading Mr. Turgenev's story" Asya "". Meanwhile, in...

- After the end of the Vienna Council, Emperor Alexander Pavlovich decides "to travel around Europe and see miracles in different states." Accompanied by him...

- The subject of the story is the “life-existence” of representatives of the Stargorod “cathedral priesthood”: Archpriest Savely Tuberozov, priest Zakhary Benefaktov and deacon Achilles Desnitsyn. Childless Tuberozov...

- Iosaf Platonovich Vislenev returns to the county town, convicted in the past on a political case. He is met by his sister Larisa, Alexander's ex-fiancee...

- As time passed, Yakov Sofronych understood: it all started with the suicide of Krivoy, their tenant. Before that, he quarreled with Skorokhodov and ...

- When I try to imagine Belikov, I see a little man locked in a cramped little black box. The man in the case... What, it seemed...

- The writer Muraviev wrote a story about labor for one of the Moscow magazines, but nothing came of it. Muravyov thought...

- In the old castle of Abo (Finland) lived an old brownie. He was friends only with the brownie from the cathedral and the old gatekeeper of the castle ...