Collective leadership. After Stalin's death. Collective leadership Topic 6 of the USSR during the years of collective leadership

The fragility and weakness of his personal power did not prevent Malenkov from promoting his economic program with a certain determination. On August 8, 1953, he made an important speech to the Supreme Soviet, a speech that was dominated by foreign policy issues, but which was also characterized by innovative approaches to domestic policy.

The new government intended to address the main identified problems in a decisive manner. It is necessary, Malenkov said, to give new importance to the needs of consumers, to raise the standard of living, and for this, to increase agricultural production. The availability of consumer goods should also be expanded. Malenkov emphasized the fact that the USSR had a “powerful and technically superior heavy industry,” and noted: “Until now, we have not had the opportunity to develop the light and food industries at the same pace. At the moment, we can do this and, therefore, we are obliged, in order to ensure a more rapid improvement in the material and cultural standard of living of the people, to accelerate the development of light industry by any means.”

Thus, the theme of the welfare of the people was placed at the center of the new government course, which meant a clear turn in relation to the past. From now on the ratio

Chapter 9. Formation of blocks and the evolution of their relationships 815

between the global growth of Soviet GDP and the production of consumer goods became one of the criteria for both measuring the effectiveness of government activities and assessing its general directions. However, at that stage everything happened within the framework of the reform project, which did not in any way change the concept on which the Soviet economy was built. Therefore, the discussion quickly (and in good time) turned into a technical discussion about forms of optimization of production and developed in accordance with the priorities that Malenkov clearly outlined in 1953, but from which his successors later distanced themselves.

In terms of foreign policy, the consequences of the turn were significant. Malenkov praised Soviet power, which had increased with the production of the hydrogen bomb, but gave his words a distinctly pacifist character aimed at reducing international tension. He spoke at length about the changes that had taken place since Stalin's death and the atmosphere of hope that had spread throughout the world: “It is our deep conviction that at present there is no unresolved or controversial issue that cannot be resolved peacefully through mutual agreement between interested parties... We are for peaceful coexistence between the two systems.”

This was the thesis that Malenkov supported until he took a position on March 12, 1954 (opposite to the opinion of the military leadership and a significant part of the political nomenklatura of the USSR), which contained the assertion that a nuclear war would be a disaster for all of humanity, because it would mean its end. A thesis that a few months later, when the power of the chairman of the government began to weaken, was refuted by both Khrushchev and Voroshilov - they argued that a nuclear war would lead, first of all, to the final destruction of capitalism.

This atmosphere, which was conveyed by the Soviet writer Ilya Erenburg in his novel “The Thaw” (starting with its title), which not coincidentally appeared in 1954, was perceived throughout the world. Situations that had dragged on for years were quickly resolved; New areas for discussion opened up. This did not always take place in a calm atmosphere and without controversy. The aspirations of a few in the collective leadership had difficulty trumping the mentality of many who were nostalgic for Stalinism. And yet, all the months, from the spring of 1953 to the second half of 1955, were marked by a clear desire to peacefully resolve differences rather than aggravate them.

Part 3. Cold War

The foreign policy of the “collective leadership” was dominated primarily by the search for dialogue with the West: from a position of strength and without mental reservations in those months when Malenkov was in power; from a position of strength and with numerous mental reservations - after the beginning of Khrushchev’s hegemony. It is even more interesting to note that while Stalin concentrated his attention primarily on European problems or on aspects related to direct conflict with the United States, his successors immediately expanded their range of interests. The feeling that the situation in Europe had already stabilized, the formation of the movement of non-aligned countries and the beginning of the stage of rapid decolonization seemed to pose new problems for the Soviet Union. Therefore, his international policy quickly acquired a global scale that had never existed under Stalin, and his diplomacy asserted itself with greater confidence and different intonations in the Mediterranean, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, East Asia, China and Pacific region. In a certain sense, the legacy of power left by Stalin was being collected: since the European front was strengthened (assuming that this was the case), it was possible to look at the future of the USSR no longer as the future of a superpower limited to Eurasia, but as a superpower capable of forcing people to reckon with themselves. worldwide.

It could be noted that the expansion of the sphere of interests was in conflict with the declared intentions towards the West, aimed at defusing international tension. In fact, this remark is not without foundation, and it indicates the limits within which a policy of friendly relations with the Western Union could develop. In fact, it was precisely the expansion of horizons that made it impossible in those years for the Soviets to have an equal presence with the West in economic and military terms. It was about the desire to be a truly global power, which, however, had to take into account real facts, and which conflicted with the fact that the United States was already a global power, economically present throughout the world and militarily still ahead of the USSR for several years.

These were the “new frontiers” of the bipolar system.

Some people wanted to see it as a continuation of the logic of the Cold War. Although episodes characterized by this logic were repeated in subsequent years with varying degrees of intensity, and although with

Chapter 9. Formation of blocks and the evolution of their relationships 817

Soviet policy can be interpreted as a response to Dulles's policy - the creation of a system of alliances along the entire border of the zone of Soviet influence, these new borders gave new meaning and new significance to the bipolar clash. The years of coexistence-competition were approaching: still confrontation, but softened by the desire for coexistence.

The first manifestation of new Soviet orientations was the unblocking (which, incidentally, Eisenhower also wanted) of the armistice negotiations in Korea. Interrupted a long time ago, they resumed on June 20, 1953, also thanks to the initiative of the Soviet side, and on July 27 ended with the signing of a truce in Pan-munzhong.

In his speech on August 8, Malenkov declared that the Soviet Union was renouncing its claims against Turkey dating back to 1944. At the same time, normal diplomatic relations with Yugoslavia and Greece were resumed. Good intentions were declared towards Iran, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and all countries of the Western system.

On January 25, 1954, the Berlin meeting of the foreign ministers of the four great powers that occupied Germany began. Although it had no primary purpose, the meeting was an important turn that Dulles reluctantly accepted. From the first day of work, Molotov proposed that at the second stage a meeting of the five (with the participation of People's China) be convened to discuss the main topics of international detente. The proposal was revised during the meeting due to Dulles's refusal to agree to a meeting, which would mean indirect recognition of People's China by the American side. However, at the end of the meeting, a compromise formula was found regarding the need to discuss a peace treaty with Korea, convening a meeting in Geneva on April 26 with the participation of all parties interested in resolving the Korean conflict, but also the Indochina issue. A compromise was found in a formula that separated the inviting powers from the invited ones, with the clarification that the participation of the latter (i.e. People's China and North Korea) would not mean diplomatic recognition of these two countries. Despite this reservation, the result was important because Dulles recognized that the Korean question could not be discussed without Chinese participation, and the French recognized that the Indochina question had already become an international problem and not just an internal problem of the French colonial system.

The meeting in Geneva began its work at the moment of the most heated political debate in France on the EOS. It's long

Part 3. Cold War

and unsuccessfully discussed the Korean question. The problem of Indochina was still discussed unsuccessfully until Pierre Mendes-France was appointed Chairman of the Council of Ministers in France. Although this is not the place to analyze this topic, it should, however, be emphasized that the arrival of Mendes-France in Geneva gave impetus to the negotiations. After a series of high-level contacts, a package of agreements was signed on July 20-21 between France and various antagonists to its dominance in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

From the point of view of the general balance of forces between the powers, the Geneva Agreements reflected new conditions arising from the transition period in the system of international relations. The fact that the meeting took place and concluded in a constructive manner regarding at least one of the two topics discussed was in itself a positive development. After the peace treaties of 1947 and the Korean Armistice, for the first time the conflicting parties reached a compromise on an important issue.

The participation of the People's Republic of China confirmed the role that it had already acquired in the life of Asia. It was not yet universal recognition, but rather a recognition bitterly contested by the United States, but the moderation of Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai showed that China could also play a decisive role in Asia, a role that its neighbors such as India, Vietnam and itself The Soviet Union could not be ignored. Great Britain fully fulfilled its task of mediation and establishing balance. Her contribution was valuable and contributed greatly to her rapprochement with France, the results of which would become apparent soon after the failure of the EOC treaty.

The Soviet Union pushed the Vietnamese into a compromise by sacrificing considerable military successes. Soviet diplomacy could evaluate the results as the fruit of its own activities. Dulles, who was almost always represented by Walter B. Smith throughout the negotiations, did not prevent the reconciliation from taking place, as if it were an event that only indirectly concerned the United States. However, they were already preparing to accept the (possibly bitter) legacy of liberating the French from their obligations and were preparing to sign the SEATO Treaty. Thus, their aloofness was only a façade, covering up both their intention not to have direct diplomatic relations with the People's China - at a time when high-level protests were coming from Taiwan (with the support of the powerful Chinese lobby) about the concessions made

Another target of mass repression was the population of the western regions included in the USSR in the pre-war years - the Baltic states, Western Ukraine, Belarus, and Bessarabia. The incomplete “Sovietization” of these countries and the active partisan movement, which could not be suppressed for many years, were considered by the Stalinist leadership as a threat to the security of the USSR. In addition to continuing operations against “kulaks”, “bandits and their accomplices”, “OUN members”, which began in the previous period, in 1951 the MGB prepared and carried out the eviction of several thousand members of the religious sect Jehovah’s Witnesses to Siberia.

Against the backdrop of new purges in the country and increased military mobilization, the situation in the highest echelons of power looked quite stable, especially compared to 1949. Stalin's policies towards his comrades in the early 1950s combined traditional methods of control and intimidation with relative moderation. On this basis, a certain consolidation of the Politburo took place and the elements of “collective leadership” were strengthened. These trends increasingly determined the evolution of supreme power and laid the foundations of the post-Stalin political system.

"Seven" as a prototype of "collective leadership"

As a result of the destruction of the “Leningraders” and various changes in the Politburo and the leadership of the Council of Ministers, by the beginning of 1950, Stalin’s entourage had the following configuration. Two of Stalin's old associates, A. A. Andreev and K. E. Voroshilov, although they remained members of the Politburo, did not actually participate in its work. Andreev was seriously ill for a long time. At the beginning of 1949, the Politburo granted him a six-month leave for treatment. He was on long leave for much of 1950. During those periods when Andreev was able to work, he headed a secondary government department - the Council for Collective Farm Affairs. As a member of the Politburo, Andreev periodically voted by poll. He was removed from solving significant issues, since he was not a member of the Politburo leadership group. After February 1947 until Stalin's death, Andreev never appeared in Stalin's office. In 1949, due to growing anti-Semitism, Andreev’s wife D. M. Khazan was persecuted. First, she was transferred from the post of deputy people's commissar of the textile industry to the post of director of a research institute, and then she was even expelled from the institute with a scandal. On February 19, 1950, Pravda published an article “Against Perversions in the Organization of Labor on Collective Farms,” in which Andreev was criticized for his incorrect views on this issue. Despite the fact that Andreev immediately showed a willingness to publicly repent (a draft of Andreev’s letter to Stalin was preserved, in which he fully admitted his mistakes and asked for a meeting), on February 25, a Politburo resolution was adopted condemning Andreev for “wrong positions.” On February 28, Andreev’s repentant statement was published in Pravda.

K.E. Voroshilov was in a slightly better position. Pushed to the periphery of the system of supreme power - to the traditionally secondary role of cultural curator in the Soviet political system, Voroshilov was also limited in his rights as a member of the Politburo, since he was not part of its leadership group. At the same time, Voroshilov was also often sick and on vacation.

If Andreev and Voroshilov remained rather symbols of the revolutionary legitimacy of power, then other representatives of the “old guard” - V. M. Molotov, A. I. Mikoyan, L. M. Kaganovich were actually active members of the Stalinist Politburo. Molotov and Mikoyan, although subjected to periodic attacks, continued to perform the most important state functions and were members of all the highest party and state bodies. By the end of the 1940s, Kaganovich had largely restored his position in Stalin’s entourage. Judging by the minutes of Politburo meetings and entries in the logbook of Stalin’s Kremlin office, Kaganovich, after returning from Ukraine to Moscow at the end of 1947, was actually included in the Politburo leadership group, although no formal decision was made on this matter. As Stalin's deputy on the Council of Ministers, Kaganovich was also a member of the governing bodies of the government.

The second group of Politburo members was more numerous, following the “old men” in terms of age and time of entry into the highest structures. It also had its leaders and outsiders. Among the latter was A. N. Kosygin, who was associated with the executed “Leningraders.” Stalin saved his life and position, but deprived him of a place in the highest echelons of power. The decision to introduce Kosygin into the leadership group of the Politburo, made in 1948, after the “Leningrad affair” turned into an empty piece of paper. Although it was not formally abolished, in fact Kosygin did not participate in the work of the Politburo and after 1949 he never appeared at meetings in Stalin’s office.

Formally, in terms of the importance of the positions held, this group at the beginning of 1950 was headed by G. M. Malenkov and N. A. Bulganin. Malenkov was the only top Soviet leader (except Stalin himself) who combined key posts in the party and state apparatus. Malenkov led the work of the Secretariat and the Organizing Bureau of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks and was actually Stalin’s deputy in the party. It was in the name of Malenkov, as well as in the name of Stalin, that various kinds of appeals from ministers and local leaders were often received, intended for consideration or approval in a party manner. As deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers, Malenkov was a member of all governing bodies of the government and oversaw agriculture. Bulganin, as already mentioned, from April 1950 served as Stalin's first deputy in the government. In practice, this meant that Bulganin received greater opportunities for contacts with Stalin. During Stalin's vacation in August-November 1950, it was Bulganin who sent him memos, in which he reported on the main issues considered at meetings of the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers, on upcoming draft government resolutions, and on the work of the Politburo steering group on foreign policy issues.

After his transfer to Moscow, N. S. Khrushchev quickly increased his participation in the activities of the highest party and state structures. His appointment to the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks significantly changed the balance of power in this body of power, where Malenkov had previously reigned supreme. Unlike other secretaries (M. A. Suslov, P. K. Ponomarenko, G. M. Popov), Khrushchev was a member of the Politburo. Although no formal decision was made to include Khrushchev in the Politburo leadership group, in fact, judging by the Politburo minutes, he was introduced to it around July 1950. Khrushchev regularly met in Stalin's office. Even more significant (and somewhat unexpected for historians, who always believed that Khrushchev, in contrast to Malenkov, was focused on working in the party apparatus) was Khrushchev’s active participation in the work of government structures. Despite the fact that Khrushchev did not formally hold any positions in the Council of Ministers, already in 1950 he regularly took part in meetings of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers and occasionally in the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers, and in 1951–1952 he was a permanent participant in meetings of both bodies. In January 1951, Khrushchev was also entrusted with overseeing the work of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine.

Judging by many data, L.P. Beria not only retained his positions, but even strengthened them. For the pragmatic Stalin, it was of fundamental importance that under the leadership of Beria the Soviet atomic project was successfully implemented. As Stalin’s security chief N.S. Vlasik recalled, in 1950 Beria came to Stalin in the south “with a report on the completion of the task for the First Committee of the Council of Ministers and showed a film about the completed tests of the domestic atomic bomb. This was a turning point in Stalin's attitude towards Beria. After two years of rather disdainful attitude towards Beria, which he did not hide, Stalin again returned his former location to him. Comrade Stalin emphasized that only Beria’s participation could bring such brilliant results.”

Vlasik’s evidence of Stalin’s special affection for Beria, observed at the end of 1950, is confirmed by the next reorganization of the highest government structures, which Stalin carried out after returning from vacation at the beginning of 1951. On February 16, 1951, the Politburo adopted a resolution on the formation of the Bureau for Military-Industrial and Military Issues under the Council of Ministers of the USSR under the leadership of Bulganin. The new Bureau was entrusted with managing the work of the ministries of aviation industry, armaments, military and naval ministries. The Bureau, in addition to Bulganin, included the heads of the listed departments. The Bureau coordinated the activities of almost all areas of military and military-industrial development, except for the atomic project. The creation of the Bureau of Military-Industrial and Military Affairs was associated with the intensification of the arms race after the outbreak of the Korean War. The Bureau has become one of the most important structural divisions of the Council of Ministers. However, for Bulganin, the appointment to a new responsible post actually turned out to be a transfer to departmental work, accompanied by the loss of the functions of Stalin’s first deputy on the Council of Ministers. On the same day, February 16, 1951, the Politburo adopted the following resolution:

“The chairmanship of the meetings of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers of the USSR shall be entrusted in turn to the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Comrade. Bulganin, Beria and Malenkov, instructing them also to consider and resolve current issues. Resolutions and orders of the Council of Ministers of the USSR shall be issued signed by the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR comrade. Stalin I.V.”

This decision restored the previous order of collective chairmanship at government meetings and actually deprived Bulganin of the status of first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. This was followed by the expansion of the functions of the Presidium and the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers. On March 15, 1951, the Politburo decided to liquidate many of the previously existing sectoral Bureaus of the Council of Ministers (fuel industry, agriculture and procurement, transport and communications, metallurgy and geology, culture). Issues that were previously resolved by these bureaus were subject to consideration directly by the Bureau of the Presidium and the Presidium of the Council of Ministers. In addition, Stalin personally introduced a clause into this resolution that demonstrated Beria’s growing influence. He was required to “dedicate half of his working time to business No. 1, No. 2 and No. 3.” The talk, obviously, was about atomic, missile and radar projects.

The motives for Stalin's actions in this, as in many other cases, are difficult to determine. Beria said something about how the decision was made to introduce collective chairmanship and lower Bulganin’s status. In a letter sent to members of the top Soviet leadership on July 1, 1953 from prison, Beria, addressing Bulganin, stated: “Nikolai Alexandrovich! I have never done anything bad to you […] When Comrade Stalin suggested that we re-establish the order of chairmanship, Comrade G.M. Malenkov and I convinced that this was not necessary, that you were coping with the job, and we would help so we’ll help.” These statements by Beria contained important plausible points. Firstly, Stalin, as follows from Beria’s words, motivated his proposal to deprive Bulganin of the functions of chairman by the fact that Bulganin could not cope with his duties as first deputy. Secondly, Stalin discussed this issue in one form or another with Beria and Malenkov. It is obvious that even if Beria and Malenkov really demonstrated their “political modesty” to Stalin and refused to co-chair government meetings, objectively this decision was in their favor. It cannot be ruled out that through various methods they contributed to a return to the previous order of “collective work.” This, of course, does not mean at all that Stalin acted at someone’s instigation and did not have his own motives, business or psychological, for such a step.

Having again dispersed the operational leadership of the government, Stalin acted in line with his usual policy of maintaining a certain balance of power and competition in the Politburo. It is also possible that Stalin was dissatisfied with Bulganin's business qualities. Finally, Stalin's psychological state may have been an important factor. Experiencing increasing health problems and returning from his last and one of the longest vacations, he again demonstrated to his associates (and himself) that he did not intend to let go of the levers of power and did not need a first deputy. In any case, the idea of nominating Stalin's first deputies from now on until his death no longer arose. Finally, the decision to require Stalin’s signature even on such relatively minor documents as orders of the Council of Ministers was also of a purely political, demonstrative nature. Having deprived his deputies of the right to sign orders, Stalin was unlikely to pursue business goals. The decision-making process could only become more complicated as a result of this action. However, for Stalin himself, the sole right to sign could be a certain symbolic compensation, a defensive reaction of an aging dictator, forced to retire from many affairs.

There were several signs of such a retreat. It is estimated, for example, that if before the war, in 1939-1940, the log of visitors to Stalin’s Kremlin office recorded approximately two thousand visits per year, in 1947 - approximately 1200 visits, then in 1950 - 700, and in 1951-1952 - only 500 visits each. This was largely due to a significant increase in the duration of Stalin’s vacations, which, in turn, also served as an indicator of a decrease in his work activity. In 1945, Stalin spent more than two months in the south, in 1946–1949 from three to three and a half months, in 1950–1951 for four and a half months. Moreover, during the vacation period of 1951, Stalin did not appear in his office for more than six months - from August 9, 1951 to February 12, 1952. This was due to the fact that after a vacation that lasted almost until the end of December, Stalin fell ill with influenza in January 1952.

In Stalin's presence in Moscow, meetings of the Politburo leadership group were held either in his Kremlin office or (more and more often over time) at his dacha. From a formal point of view, many of these meetings cannot be identified definitely - they can be considered meetings of the Politburo, and meetings of the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers, and meetings of the narrow leadership group of the Politburo. Decisions made at such meetings could also be formalized in different ways: as decisions of the Politburo or resolutions of the Council of Ministers. Some conclusions about the order of decision-making in the last period of Stalin’s life can be drawn based on a comparison of logs of visitors to Stalin’s Kremlin office and authentic minutes of Politburo meetings.

On behalf of the Politburo, mainly personnel decisions were drawn up (the corresponding resolutions of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks were approved), as well as resolutions on international affairs introduced by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Foreign Policy Commission. Judging by the passage of the Foreign Ministry's questions, in the last year of Stalin's life there were several ways to approve decisions on behalf of the Politburo. Most of these decisions were discussed and made at meetings in Stalin's office in the Kremlin. For example, many projects submitted for approval by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were formalized as Politburo resolutions after Vyshinsky informed Poskrebyshev that their approval had taken place on a certain day. As a rule, the dates called by Vyshinsky corresponded to the days of meetings in Stalin’s office in which Vyshinsky himself took part. Thus, according to Vyshinsky, the Foreign Ministry’s questions were approved on March 22, 31, May 19 and 24, June 9, 25, August 20, 22, 1952. During these days, Vyshinsky was present in Stalin's office along with members of the Politburo.

In a number of cases, on the days indicated by Vyshinsky, there were no meetings in Stalin’s office. Such decisions could have been made at Stalin’s dacha, either with or without Vyshinsky’s participation. For example, on the draft resolution on the dismissal of F. T. Gusev from the post of Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, issued on August 15, 1952, Vyshinsky wrote: “To Comrade A. N. Poskrebyshev, please formalize. The draft resolution was drawn up in accordance with the instructions received on 13.VIII.” On August 13, as follows from Vyshinsky’s notes, preserved in the original minutes of Politburo meetings, several Ministry of Defense proposals were approved. This suggests that on this day a meeting of the top leadership took place with the participation of Vyshinsky or a meeting between Stalin and Vyshinsky. However, no one gathered in Stalin’s Kremlin office on August 13.

In some cases, Vyshinsky could learn about decisions made on Foreign Ministry issues from other members of the Politburo, primarily Molotov. For example, on the draft of one of the resolutions, Vyshinsky made a note on June 6, 1952: “Comrade. Poskrebyshev A.N. Please register. According to Comrade V.M. Molotov, approved by Comrade Stalin.” He reported about two other projects: “Comrade. Poskrebyshev A.N. According to comrade. Molotov V.M., approved by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on 17.VI. 1952 Please register." On none of these days, neither June 6 nor June 17, were there any meetings in Stalin’s office. Apparently, Molotov coordinated these decisions with Stalin personally or reported to Vyshinsky the results of the meetings at Stalin’s dacha. Finally, on a number of Foreign Ministry projects, members of the Politburo voted in a round-robin manner, without meetings. This also required Stalin's consent. So, on July 23 (apparently at a meeting in Stalin’s office in the Kremlin), Vyshinsky received Stalin’s permission to resolve a number of Foreign Ministry issues by voting in a round-robin manner. This vote, in which Molotov, Malenkov, Bulganin, Kaganovich, Mikoyan, Khrushchev, and Beria participated (the latter’s consent was reported by his assistant Ordyntsev), was held in portions on July 25 and August 1–2.

The disorder of the Politburo's decision-making procedures was largely due to the fact that Stalin, despite the huge flows of information and the decline in his own performance, still sought to control the widest possible range of issues. Top Soviet leaders spent a significant portion of their working time either in Stalin's office or at Stalin's dacha, subject to his personal schedule and whims. Regular Politburo meetings with pre-agreed agendas were not held. All this led to increased chaos and discontinuities in the decision-making process. One of the important mechanisms for overcoming them was the use of methods of “collective leadership,” which most clearly manifested themselves during periods of long Stalinist vacations.

As can be seen from the original minutes of Politburo meetings, in the absence of Stalin, issues to be considered by the Politburo were discussed at their meetings by the Politburo leadership group. In 1950 and until the autumn of 1952, it included Molotov, Mikoyan, Kaganovich, Malenkov, Beria, Bulganin, Khrushchev. In documents during this period it was called the “seven” (“eight” together with Stalin). The authentic minutes of the Politburo meetings make it possible to record some differences in the work procedure of the “seven” during Stalin’s holidays compared to the procedure for the meetings that took place in Stalin’s presence. Judging by the wording of many decisions, the “seven” without Stalin worked as a truly collective body. She discussed decisions, created commissions for additional study and preparation of draft resolutions. For example, on September 17, 1951, Beria, Bulganin, Kaganovich, Molotov (the remaining members of the leadership group were, apparently, on vacation), having considered the issue of the USSR’s participation in the conference on promoting trade in Asia and the Far East, decided: “Entrust TT . Vyshinsky and Menshikov within two days taking into account the exchange of views rework, and comrade Molotov to first consider and submit proposals on this issue to the Politburo.” On November 15, 1951, Beria, Kaganovich, Malenkov, Mikoyan, Khrushchev made the following decision on behalf of the Politburo on the issue of special German settlers: “Entrust comrade. Ignatiev, Gorshenin, Kruglov and Safonov to thoroughly understand this issue within two weeks and rework the draft resolution submitted by the USSR Ministry of State Security taking into account the exchange of opinions at Politburo meetings". Similar examples can be continued. It is important to emphasize that during the periods when Stalin was present in Moscow, such wording was almost never found in the protocols. Of course, the decisions made by the leadership group were sent to the south for approval by Stalin. Many Politburo decisions bear marks from Poskrebyshev, who traveled south with Stalin, indicating Stalin’s consent or his amendments. Despite this, the order of work of the “seven” in the absence of Stalin approached the usual order of work of the Politburo as a collective body of power. By getting rid of Stalin's direct supervision, his comrades actually restored the meeting procedures that were characteristic of the Politburo until the mid-1930s, until Stalin consolidated his grip on power as the sole dictator. It was this already proven order of “collective leadership” that was in demand immediately after Stalin’s death.

Perhaps even more important for a certain consolidation of the “collective leadership” were the regular and frequent meetings of the highest government bodies - the Presidium and the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, which continued the practice of the previous period. The personnel of the G8 of the Politburo and the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers completely coincided. At the time of its creation in April 1950, the Bureau (in addition to Stalin) included five members of the Politburo - Bulganin, Beria, Kaganovich, Mikoyan, Molotov. A few days later Malenkov joined them. From September 1950 to the end of 1952, Khrushchev constantly participated in the meetings of the Presidium and Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers. A characteristic feature of the work of these government structures was that Stalin never took part in their meetings, even while in Moscow. Meanwhile, the Presidium and the Bureau of the Presidium of the Council of Ministers met regularly and often. From the beginning of April to the end of 1950, the Bureau of the Presidium met 38 times. 38 meetings of the Bureau were held in 1951 and 43 in 1952.

Thus, the Politburo leadership group met several times a month to discuss issues of national importance without Stalin. This practice of “collective leadership” was carried out within the framework of a stable leadership structure that operated on the basis of a well-established regular procedure (fixed schedule, advance preparation of agendas, etc.). Together with Politburo meetings held during Stalin's holidays, the work of government bodies contributed to the development of fundamentally important skills, if not political, then administrative interaction of the Politburo leadership group. As a result, in the depths of the Stalinist Politburo, the prerequisites for the denial of one-man dictatorship were formed, which were in demand immediately after Stalin’s death. An important factor in this denial was the desire to prevent a repetition of the repressions and political humiliations that Stalin's associates were subjected to until his death.

New attacks: “agricultural cities” and “Mingrelian affair”

The formation of a stable balance of power in the top Soviet leadership did not lead to the end of Stalin's attacks against members of the Politburo, although none of them had such serious consequences as the “Leningrad affair”. The most significant and well-known actions of 1951 were the study of N. S. Khrushchev in connection with his article on the consolidation of collective farms and the “Mingrelian affair,” largely directed against Beria.

Khrushchev’s article “On construction and improvement on collective farms” was published in the newspapers “Pravda”, “Moskovskaya Pravda” and “Socialist Agriculture” on March 4, 1951. It put forward projects for the creation of “agricultural cities” and “collective farm villages”, where peasants from small villages and hamlets were to be evicted. The very next day, Pravda published an explanation that the article was published for discussion, but due to the fault of the editors, this was not indicated. This Pravda article concealed the beginning of an attack against Khrushchev, which was launched by Stalin, dissatisfied with the initiatives of his comrade-in-arms. Immediately after publication, Stalin reprimanded Khrushchev. On March 6, Khrushchev wrote a letter of repentance to Stalin:

“[...] After your instructions, I tried to think through these issues more deeply. After thinking it over, I realized that the whole speech as a whole was fundamentally wrong. By publishing an incorrect speech, I made a grave mistake and thereby caused damage to the party. This damage to the party could have been prevented if I had consulted the Central Committee. I did not do this, although I had the opportunity to exchange opinions in the Central Committee. I also consider this my grave mistake. Deeply experiencing the mistake I made, I think about how best to correct it. I decided to ask you to allow me to correct this mistake myself. I am ready to appear in print and criticize my article […] I ask you, Comrade Stalin, to help me correct the gross mistake I made and thereby, as far as possible, reduce the damage that I caused to the party with my incorrect speech.”

However, Stalin ignored these humiliating requests. According to Molotov’s memoirs, Stalin gave instructions to prepare a document criticizing Khrushchev: “Stalin says: “We need to include (in the commission for preparing the draft decision.” - Auto.) and Molotov, so that they would give it to Khrushchev stronger and work it out harder!”” The preparation of the document was carried out, according to Molotov, under the leadership of Malenkov. These testimonies of Molotov are also confirmed by the memoirs of D. T. Shepilov that the document was prepared in the agricultural department of the Central Committee, which was headed by A. I. Kozlov, who was close to Malenkov. Shepilov argued that the tone of the paper was initially harsh and politically pointed, and Khrushchev's statements were characterized as "leftist".

It seemed that a serious threat was hanging over Khrushchev's political career. Soon, a draft closed letter from the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, “On the tasks of collective farm construction in connection with the consolidation of small collective farms,” was submitted for Stalin’s approval, intended for distribution to localities, up to the district party committees. In the original minutes of the Politburo meetings, this document was preserved with Poskrebyshev’s note: “Not approved. Recognized as unsatisfactory. March 1951". The extensive changes that Stalin made to the project explain the reasons for its rejection. The most significant thing was that Stalin crossed out an entire paragraph containing detailed criticism of Khrushchev’s article and inserted a moderate phrase: “It should be noted that similar mistakes were also made in Comrade Khrushchev’s famous article “On construction and improvement on collective farms,” which he fully admitted the fallacy of his article." Stalin’s sentiments, manifested in this edit, are also confirmed by Molotov’s memoirs: “When we brought our project, Stalin began to shake his head […] Then he looked: “We need to be softer. Soften." According to Shepilov, A.I. Kozlov, one of the authors of the original draft, informed him that “Comrade Khrushchev had an explanation with Comrade Stalin” and therefore work on a critical article about Khrushchev’s speech was stopped.

In a softened form by Stalin's edits, the closed letter was approved by the Politburo on April 2, 1951. Of course, for Khrushchev such criticism was a significant blow, especially since on April 18 the Politburo decided to read the letter even at meetings of primary party organizations. This mistake of Khrushchev was also mentioned in Malenkov’s report at the 19th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in October 1952. It is no coincidence that Khrushchev himself in 1958, as soon as he consolidated his hold on power after Stalin’s death, achieved the cancellation of this letter from the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks as erroneous. However, Stalin did everything necessary to preserve Khrushchev’s previous positions and did not allow him to be completely discredited. Khrushchev, in addition to his previous “sins,” simply acquired another new one, which made him even more obedient and manageable.

The so-called “Mingrelian affair” had similar consequences for Beria, the initiator and organizer of which, as documents clearly indicate, was Stalin; Events developed as follows. On September 26, 1951, Stalin, who was on vacation in Georgia, received the Minister of State Security of Georgia N. M. Rukhadze. In a conversation at the dinner table, as the arrested Rukhadze later testified, Stalin so far generally touched on the topic of the dominance of the Mingrelians in Georgia and their patronage by Beria. Some time later, the head of Stalin’s security, N.S. Vlasik, informed the leader about complaints about bribery when entering Georgian universities. Vlasik’s signals were completely understandable. He was in a conflicting relationship with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which was supervised by Beria, and with pleasure not only demonstrated to Stalin his integrity and vigilance, but indirectly compromised Beria, who, as everyone knew, patronized Georgia. As for Stalin, Vlasik’s rather vague information could well have gone past his ears if Stalin himself, as evidenced by his meeting with Rukhadze, had not been thinking about the purge in Georgia at that time. Stalin became interested in Vlasik’s information and instructed Rukhadze to investigate the issue.

On October 29, 1951, Rukhadze reported to Stalin that the information about bribery in general was not confirmed. However, this no longer mattered. Stalin set his sights on organizing a new campaign and inventing a pretext for it was a matter of time. On November 3, Stalin called Rukhadze and invited him to prepare a note on the patronage of the second secretary of the Communist Party of Georgia M.I. Baramia to the former prosecutor of Sukhumi Gvasalia, who was accused of bribery. Rukhadze completed the task and prepared a document from which it followed that Baramia covered up the crimes of officials of Mingrelian nationality. The case moved quickly. Already on November 9, 1951, the Politburo adopted a resolution “On bribery in Georgia and on the anti-party group of Comrade Baramia.” It spoke of the existence in the leadership structures of Georgia of a group of Mingrelian nationalists led by Baramia, which patronized bribe-takers (the Gvasalia case was cited as an example) and placed its own people in leadership positions everywhere:

“There is no doubt that if the anti-party principle of Mingrelian patronage, practiced by Comrade Baramia, does not receive the proper rebuff, then new “chiefs” will appear from other provinces of Georgia[...], who will also want to patronize “their” provinces and patronize the guilty elements there, so that This will strengthen your authority “among the masses.” And if this happens, the Communist Party of Georgia will disintegrate into a number of party provincial principalities that have “real” power, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Georgia and its leadership will only be left with empty space.”

Baramia, as well as a number of other leading officials of the republic, were removed from their posts. The style of the document, as well as the fact that the original minutes of the Politburo meetings contain a copy of the draft resolution written down by Poskrebyshev (undoubtedly dictated by Stalin) and another copy of the typewritten draft with Stalin's edits, indicate that the resolution was prepared by Stalin himself.

It is easy to see that the “Mingrelian affair” developed according to a similar scenario to the recent “Leningrad affair.” Formally, it all started with standard accusations of abuse of power and condemnation of the practice of political protectionism - “patronage”. The next step, which was not long in coming, was the arrest of the disgraced leaders and the fabrication of cases about their “anti-Soviet” and “espionage” activities. On November 16, 1951, at the direction of Stalin, the Politburo resolution “On the eviction of hostile elements from the territory of the Georgian SSR” was adopted. In total, 11.2 thousand people were deported to remote areas of the country. 37 leaders of the republic were arrested.

Having received the necessary materials, Stalin took the next step, which was undoubtedly planned in advance - he completely replaced the leadership of Georgia. As follows from the certificate deposited in Stalin’s personal archive, on March 25, 1952, from 18:00 to 22:25, and on March 27, from 22:00, meetings of the Politburo were held, at which members and candidate members of the Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia, summoned to Moscow, were present, as well as Deputy Chairman of the CPC M. F. Shkiryatov, Minister of State Security S. D. Ignatiev and head of the department of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, who oversaw the activities of regional party organizations, N. M. Pegov. The result of these meetings was a new Politburo resolution of March 27, 1952 on the state of affairs in the Communist Party of Georgia. The resolution stated that the “Baramia group” “intended to seize power in the Communist Party of Georgia, while counting on help from foreign imperialists.” Responsibility for the fact that such an “anti-Soviet organization” operated unhindered for several years and was discovered only on instructions from Moscow was placed on the leadership of the Communist Party of Georgia. As a result, K. N. Charkviani was removed from the post of First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia. In his place was appointed the young leader of Abkhazia A.I. Mgeladze, to whom Stalin had long demonstrated his affection and support in his rivalry with Charkviani. Documents indicate that this second decree on Georgia, like the first, was prepared, at least, with the active participation of Stalin. It was he who gave the title to the resolution. Poskrebyshev made an amendment to the draft document, which was undoubtedly dictated by Stalin.

After the decision of March 27, the fabrication of the case about the “Mingrelian nationalist group” received new impetus. A team of investigators arrived from Moscow to help Rukhadze, teaching the executioners from the Georgian MGB lessons in torture skills. Relying on the support of Stalin, Rukhadze launched purges in the republic. On this basis, he came into conflict with Mgeladze. Clearly overestimating his strength (more precisely, misjudging Stalin’s intentions), Rukhadze ordered to extract testimony against Mgeladze from the arrested. He sent fabricated interrogation reports to Stalin. Stalin's reaction was unexpected for Rukhadze. Stalin prepared a response, addressed, however, not to Rukhadze, but to Mgeladze and members of the Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia. Stalin's letter said:

“The Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) believes that Comrade Rukhadze has taken the wrong and non-party path, attracting those arrested as witnesses against the party leaders of Georgia […] In addition, it should be recognized that Comrade Rukhadze does not have the right to bypass the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Georgia and the government of Georgia, without whose knowledge he sent materials against them to the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, since the Ministry of State Security of Georgia, as a union-republican ministry, is subordinated not only to the center, but also to the government of Georgia and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia (Bolsheviks).

Fulfilling Stalin's instructions, Tbilisi decided to remove Rukhadze from the post of Minister of State Security. On June 9, 1952, this decision was approved by the Politburo in Moscow. However, Stalin kept the situation in limbo for some time, not agreeing to Rukhadze’s arrest. On June 25, 1952, Stalin telegraphed the leaders of Georgia, who were impatient to finally deal with their enemy: “We consider the question of the arrest of Rukhadze to be premature. We advise you to complete the delivery and acceptance of cases (according to the Ministry of State Security of Georgia. - O. X.) to the end, after which to send Rukhadze to Moscow, where the issue of Rukhadze’s fate will be resolved.” Soon Rukhadze was actually summoned to Moscow and arrested there. This scenario was fully consistent with the nomenklatura rules of the Stalinist period. The fate of officials of Rukhadze’s rank could only be decided in the center.

The arrest of Rukhadze indicated that the goal of Stalin, who organized the “Mingrelian affair,” was not to increase mass repressions in Georgia, but to remove from power and destroy only one clan of Georgian officials associated with Beria. Of course, the “Mingrelian affair,” like all other Stalinist actions of this kind, was multifunctional. The resolution of November 9, condemning “patronage” and a menacing reminder of the immutability of strict centralization of power, was sent to all party and state leaders at the top and middle levels, including the first secretaries of the Central Committee of the Communist Parties of the union republics, regional and regional party committees. Thus, the “Mingrelian affair” was another campaign against centrifugal tendencies in the apparatus. However, according to the general opinion of historians, the “Mingrelian affair” was largely directed against Beria and his client network in Georgia. With particular cynicism, Stalin instructed Beria to hold a plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia in April, at which he was to lead the “exposure” of his recent charges. Beria himself undoubtedly perceived repression in Georgia as a personal threat. Immediately after Stalin’s death, he achieved the cessation of the “Mingrelian affair”, the release and promotion of arrested “Mingrelians” to leadership positions.

Despite the danger looming over Beria, for him personally the “Mingrelian affair” ended well. Beria, like Khrushchev before him, only received another lesson and reminder of the frailty of political existence under the rule of Stalin. In the same way, for Bulganin, the “artillery case”, which unfolded simultaneously with the “Mingrelian case,” ended. On December 31, 1951, a resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR “On the shortcomings of the 57-mm S-60 automatic anti-aircraft guns” was adopted, on the basis of which a number of high-ranking military and defense industry leaders were removed from work and put on trial for “sabotage.” Bulganin, who oversaw the defense industries, as Khrushchev later claimed, was in danger, since it was he who was accused of receiving a gun with defects. However, unlike Malenkov, who suffered at one time for a similar “aviators’ case,” Bulganin retained his position. The arrested artillerymen, as well as the “Mingrelian nationalists,” were released almost immediately after Stalin’s death.

The nature of the attacks against members of the Politburo in 1951–1952 once again indicated that Stalin was quite satisfied with the balance of power that had developed in his circle, and he was afraid to upset it. Intimidating his comrades, Stalin no longer considered it necessary to bring the matter not only to physical violence, but also to official reshuffles. At the same time, all these campaigns indicated that the main instrument of political control for Stalin remained the state security organs, the leadership of which he did not let go of his hands for a minute.

“The Abakumov Case” and control over the MGB

State security agencies had been reporting directly to Stalin since at least the late 1920s. Relying on the security officers, Stalin undertook large-scale purges of the apparatus, right up to the level of the Politburo. To a large extent, this ensured Stalin's victory in the struggle for power and his establishment as a dictator. The very system of organizing the work and even rest of Soviet leaders at various levels quite legally allowed the security officers to monitor their every move. State security was in charge of not only the constant protection of party and state functionaries, but also the delivery and processing of correspondence (as a rule, sent in code), special telephone communications (the so-called HF), dachas near Moscow and in the south, supplies for party and state leaders and their families. In addition, special forms of control were used. For example, according to some evidence, in 1950, Stalin ordered the installation of eavesdropping equipment on Molotov and Mikoyan.

Relying on the state security agencies, Stalin, however, did not become their hostage. He always treated security officers with special suspicion, not only because of his character, but also because he knew well the essence of their work. Entrusting them with the dirtiest matters, Stalin had no illusions about the capabilities and moral level of this double-edged “sword of revolution.” The main method of careful control over the state security organs in the hands of Stalin was regular reorganizations and personnel purges. They were carried out, as a rule, on the basis of manipulation of the two most powerful forces of the system - the party and state security. Repressions against party functionaries were carried out by the hands of security officers, but at a certain point the punitive bodies were placed “under the control of the party,” purged and “strengthened” from top to bottom with cadres from the party apparatus. This mechanism was used to varying degrees throughout the period of Stalin's rule. It was most widely used during the period of the “Great Terror” - when Yagoda was replaced by Yezhov in 1936 and Yezhov by Beria in 1939. An obvious signal that Stalin again decided to resort to this method was the arrest of the Minister of State Security V.S. Abakumov.

While the fabrication of the “Leningrad case” was going on, which Stalin closely followed, Abakumov’s illusions about the strength of his position apparently strengthened. Stalin was generally pleased with the progress of preparations for the trial of the “Leningraders.” According to some reports, rumors even spread among Abakumov’s circle during this period about the possibility of Abakumov’s appointment to the Politburo. However, some time after the execution of the “Leningraders,” on December 31, 1950, a Politburo resolution was adopted, indicating that Abakumov’s prospects were not so obvious. According to this resolution, the number of deputy ministers increased from four to seven. Instead of Abakumov's closest collaborator M. G. Svinelupov, the head of the administrative department of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, V. E. Makarov, was nominated for the important post of Deputy Minister for Personnel. S. A. Goglidze, who was close to Beria, was transferred to Moscow as the head of the Main Security Directorate of the USSR Ministry of State Security for railway and water transport, having previously vegetated as the head of the department of the Ministry of State Security of the Khabarovsk Territory.

Some notes in the original minutes of the Politburo meetings indicate a number of important circumstances for the adoption of this resolution. It follows from them that the draft document was prepared already in August 1950. Most likely, Stalin postponed the decision on the issue of reorganization in the MGB until the completion of the trial of the “Leningraders”. In the original protocol, on the first page of the resolution, Poskrebyshev’s resolution was preserved: “Prepare. 1 copy] should be sent to Comrade Malenkov and finalized after his call.” This indicates the direct involvement of G.M. Malenkov, and therefore the apparatus of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, in the preparation of the reorganization of the MGB. In this case, Stalin used the traditional scheme - cleaning organs at the hands of the party apparatus.

The essence of the personnel changes was that Abakumov was surrounded by new people and lost some of his associates. Most likely, the party functionary Makarov, who received instructions to deal with MGB personnel, was supposed to prepare a new reorganization of this department. However, as for the fate of Abakumov himself, it cannot be argued that Stalin already in December 1950 predetermined his physical destruction. Events could well have developed according to the scenario of 1946, when Abakumov’s predecessor Merkulov, who was subjected to sharp criticism, saved not only his life, but also his position in the nomenklatura system. However, the denunciation of one of his subordinates, Lieutenant Colonel M.D. Ryumin, played a fatal role in Abakumov’s fate.

In the denunciation that Ryumin submitted to Stalin on July 2, 1951, Abakumov was accused of various crimes, mainly that he was slowing down the investigation of a group of doctors and a Jewish youth organization that were allegedly preparing assassinations against the country's leaders. The circumstances surrounding Ryumin’s statement are almost unknown. Ryumin could have submitted an application either on his own initiative or at the prompting from above. Ryumin himself, arrested after Stalin’s death, testified during interrogation that he was forced to write a denunciation by fear for his own fate. The fact is that in 1950, Ryumin forgot a folder with important documents on the official bus, for which he received a penalty on official and party lines. In addition, in May 1951, the MGB personnel department began checking information about Ryumin’s closest relatives and revealed that he had hidden a number of incriminating facts. Ryumin wrote a report on this matter, but in it he did not mention that his father traded cattle, his brother and sister were convicted, and his father-in-law served in Kolchak’s army during the Civil War. These confessions of Ryumin are similar to the truth. Let us recall that from the beginning of 1951, a new deputy minister for personnel was appointed to the MGB from the party apparatus, which clearly implied a check of the ministry’s apparatus. Ryumin's denunciation could well have been a consequence of this check initiated by Stalin. Most likely, Stalin expected to receive precisely this kind of denunciation, and therefore Ryumin’s paper immediately came to the center of attention of the country’s top leadership.

There are no documents yet available that would allow us to find out exactly how Ryumin’s statement was put into motion. Malenkov's assistant D.N. Sukhanov claimed in his memoirs that it was Malenkov who conveyed the denunciation to Stalin. It is quite possible that some of Ryumin’s initial denunciation was, with the help of someone (for example, the same Malenkov), revised and sharpened. There is no doubt, however, that any effort to discredit Abakumov would not have succeeded if it did not correspond to Stalin's intentions. On July 4, 1951, the Politburo adopted a resolution: “Instruct the Commission consisting of comrades. Malenkov (chairman), Beria, Shkiryatov and Ignatiev to check the facts stated in the statement of Comrade Ryumin and report on the results to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks. The Commission’s work period is 3–4 days.” The way this resolution is drafted gives rise to some assumptions. In the original protocol, the resolution was written in Malenkov’s hand and was not accompanied by any voting marks. This usually happened in cases where the issue was resolved at meetings between Stalin and his closest associates. Since no meetings were recorded in Stalin’s Kremlin office on July 4, 1951, it can be assumed that the issue was resolved at Stalin’s dacha. In the handwritten version of the resolution recorded by Malenkov, the head of the department of party, trade union and Komsomol bodies of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, S. D. Ignatiev, was not mentioned as a member of the commission. His name was entered by the secretary into the typewritten text of the resolution with a note: “The correction was made at the direction of Comrade Malenkov 5.VII.” Probably, the decision to include Ignatiev in the commission was made on the night of July 5 at a meeting in Stalin’s office, where Molotov, Bulganin, Beria, Malenkov were present from 0:30 a.m., Abakumov joined them from 1:00 a.m., and from 1:40 a.m. minutes - Ryumin. The urgent involvement of Ignatiev, who soon replaced Abakumov as minister, could indicate both that Stalin had not decided on Abakumov’s fate until the last moment, and that he was delaying the choice of a new minister. However, most likely, out of caution, Stalin, as usual, did not want to reveal his intentions ahead of time.

In the allotted few days, the Politburo commission, relying on Ryumin’s statement, interrogated both Abakumov himself and his deputies and heads of MGB units. As a result, Ryumin’s denunciation was recognized as objective. On July 11, 1951, the Politburo adopted a decision “On the unfavorable situation in the USSR Ministry of State Security.” Charges were brought against Abakumov on several counts. First of all, he was accused of dropping the case against the doctor Ya. G. Etinger, who was arrested in November 1950 and admitted under torture that he “had terrorist intentions” and “practically took all measures to shorten the life” of A. S. Shcherbakov, Secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, who died in 1945. Abakumov, as stated in the resolution, “recognized Etinger’s testimony as far-fetched” and ordered the investigation in this direction to be stopped. Moreover, the resolution stated that Abakumov deliberately killed Etinger in order to suppress the investigation. Abakumov allegedly ordered the sick Etinger to be placed in a damp and cold cell. “Thus, by extinguishing the Etinger case, Comrade Abakumov prevented the Central Committee from identifying an absolutely existing secret group of doctors carrying out assignments of foreign agents for terrorist activities against the leaders of the party and government,” the Politburo resolution stated. Further, Abakumov was accused of hiding from the country's top leadership the materials of the investigation into the case of Salimanov, the former deputy general director of the joint-stock company "VISMUT", who fled to the Americans, but was arrested in August 1950 in Germany, as well as in the case of the "Jewish anti-Soviet youth organization”, arrested in Moscow in January 1951, and allegedly preparing terrorist acts against the leaders of the Politburo. Finally, Abakumov was accused of violations in the conduct of the investigation - drawing up falsified interrogation reports and delaying the investigation of cases beyond the deadlines established by law.

The Politburo decided to remove Abakumov from his job as Minister of State Security and transfer his case to court. Several high-ranking MGB officials were relieved of their positions and expelled from the party. Several others were reprimanded. The resolution obliged the MGB to resume the investigation into the “terrorist activities” of a group of doctors and a “Jewish anti-Soviet youth organization.” Finally, S. D. Ignatiev was appointed representative of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks in the Ministry of State Security, which actually predetermined his subsequent appointment as the new minister. On July 13, this resolution was included in a closed letter from the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, intended for distribution to the leaders of local party organizations (from republics to regions) and MGB units. The letter (in addition to setting out the resolution of July 11) contained an appeal to party leaders to “in every possible way increase their attention and assistance to the MGB bodies in their complex and responsible work.” Such calls to strengthen party control in the MGB were reinforced by the appointment to the post of minister on August 9, 1951 of a party official - head of the department of party, trade union and Komsomol bodies of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks Ignatiev.

The charges brought against Abakumov were clearly far-fetched. Claims about violations of “socialist legality” sounded especially absurd, given that Stalin himself gave direct instructions to the security officers to use torture. The real reasons for Abakumov's removal do not need to be complicated. Periodic shake-ups were Stalin's usual way of strengthening control over the state security organs. The candidacy of the new minister was quite suitable for this purpose. Before his promotion to the MGB, 47-year-old Ignatiev made a career in party work - from the apparatus of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks he was sent as secretary of a number of regional committees, second secretary of the Communist Party of Belarus, then in 1950 he returned to the Central Committee again as head of the department that was responsible for the selection of leading party members frames. Stalin undoubtedly chose Ignatiev, as a disciplined executor of his will, who, moreover, was not burdened by the group interests of the Chekist department. Soon other party workers were appointed to responsible positions in the MGB. At the same time, a large group of career security officers were arrested. All these purges and reshuffles were led by Stalin himself.

In addition to the new balance of power between the security officers themselves and new party nominees, in the MGB, as a result of personnel changes, an intricate system of counterbalances and competition between various groupings developed. On August 26, 1951, shortly after Ignatiev's appointment, it was decided that there was a need to have two first deputy ministers of state security. The meaning of this decision becomes clearer if we consider who exactly was appointed to these posts. Equal rights as Ignatiev's deputies were awarded to two potential rivals - S. I. Ogoltsov, who worked as a deputy for Abakumov, as well as S. A. Goglidze, who was close to Beria. Both of them periodically moved from the center to local work, and then returned to Moscow. The fate of these MGB leaders after Stalin’s death also testifies to the conflictual relationship. If Goglidze, with the support of Beria, received a high post in the new Ministry of Internal Affairs, then Ogoltsov was arrested. In addition to this competing pair, at the request of Stalin and with some resistance from Ignatiev, on October 19, 1951, Ryumin was appointed deputy minister and head of the investigative unit for especially important cases. This meant that another spy appeared under Ignatiev, who not only had a reputation as a whistleblower, but enjoyed the special patronage of Stalin and, in principle, could have direct access to him. Thus, Ignatiev was tightly surrounded by assistants, whom he himself, of his own free will, was unlikely to choose as his deputies.

Stalin's leading role in all these events is beyond doubt. Despite the active role that Malenkov played in preparing the personnel purge of the MGB, it is obvious that he acted in accordance with the instructions received from Stalin. Subsequently, Stalin personally directed the investigation against Abakumov and his employees, gave instructions to Ignatiev, and edited the indictment. The last time Stalin received a report on the Abakumov case was on February 20, 1953, shortly before his death.

After removing Abakumov and appointing Ignatiev, Stalin went on vacation, where he remained for more than four months. Judging by the inventories of documents received by Stalin during this period, he regularly and in significant quantities received various reports from Ignatiev. In total, from August 11 to December 21, 1951, Stalin received from the MGB more than 160 different documents (notes, information messages), not counting the resolutions of the Politburo and the Council of Ministers concerning the MGB, and various types of encryption, the contents and authorship of which were not recorded in the inventories. Control over the state security agencies themselves and their activities remained among Stalin’s priorities.

* * *The aggravation of the international situation and the increase in the arms race in the early 1950s, Stalin's long absence from Moscow, and the general relative decline in his activity caused by deteriorating health did not significantly change the system of supreme political power that had taken root in previous years. The procedure for approval and decision-making remained essentially the same. The partial reorganization of the government apparatus (the creation of the Bureau of Military-Industrial and Military Affairs and the liquidation of a number of previous sectoral bureaus) did not affect the functions of the Council of Ministers and its powers. Equally routine was the reorganization of the party apparatus - the division of the propaganda and agitation department of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks into four departments, carried out in December 1950. The methods by which Stalin controlled his comrades remained the same. Moreover, periodic attacks against members of the Politburo (on agrarian issues against Khrushchev and Andreev, the “Mingrelian affair”, “the artillerymen’s affair”) were more of a preventive nature and did not end as tragically for Politburo members as the “Leningrad affair”.

As a result, the period from the approval of the new configuration of supreme power by the beginning of 1950 to the convening of the 19th Party Congress in October 1952 was relatively calm for the senior Soviet leaders surrounding Stalin. The day-to-day, routine management of the country in the absence of Stalin for many months contributed to the strengthening of the relative consolidation of the group of senior Soviet leaders. The Seven, which acted on behalf of the Politburo during Stalin's holidays, used the methods of "collective leadership" that were characteristic of the Politburo in the 1930s, and then ensured a relatively painless transformation of the highest power after Stalin's death. Despite the rivalry and conflicts, the leadership group of the Politburo, in the face of common threats emanating from the decrepit and unpredictable leader, behaved with restraint and caution. Politburo members clearly preferred focusing on official duties and smooth maneuvering to intrigue and mutual struggle. Taught by the “Leningrad affair,” Stalin’s comrades-in-arms were well aware that every conflict could be used by Stalin in the most unpredictable ways. The new repressions in the Politburo did not suit any of Stalin’s comrades.

However, according to all the laws of the Stalinist dictatorship, the period of relative stability should have been replaced by new attempts by Stalin to strengthen his position through personnel changes and repressions. The most significant fact in this regard was the massive purge of state security organs carried out in 1951–1952. Its most obvious goal was to maintain Stalin's personal control over the punitive apparatus at its previous high level. The question of how Stalin intended to use his sole power over the MGB remained open.

Notes:

The party was renamed from the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in October 1952 at the 19th Congress.

AP RF. F. 3. Op. 52. D. 251. L. 93.

Secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, member of the Politburo A. A. Andreev in December 1943 was appointed People's Commissar of Agriculture of the USSR.

AP RF. F. 3. Op. 52. D. 251. L. 93; Mikoyan A.I. So it was. P. 466.

RGASPI. F. 17. Op. 163. D. 1420. L. 136.

RGASPI. F. 17. Op. 3. D. 1051. L. 44.

Russian archive. The Great Patriotic War. Orders of the People's Commissar of Defense of the USSR (1943–1945). T. 13 (2–3). M., 1997. P. 332.

S. M. Shtemenko reported on the discussion of the issue with the participation of members of the Politburo in his memoirs (General Staff during the War. Book 2. M., 1974. pp. 18–21). Most likely, the discussion took place in Stalin’s office on December 6, 1944. According to the log of visits to Stalin’s office, on that day from 10 pm to 11 pm Bulganin, First Deputy Chief of the General Staff A. I. Antonov, and Chief of the Operations Directorate of the General Staff S. M. were present there. Shtemenko, People's Commissar of the Navy N.G. Kuznetsov, Chief Marshal of Artillery N.N. Voronin, Head of the Main Artillery Directorate N.D. Yakovlev. However, contrary to Shtemenko’s statements, members of the Politburo, as follows from the magazine, were absent at that time. Zhukov, who was at the front, was also not present at the meeting.

Petrov N. First Chairman of the KGB Ivan Serov. pp. 106–107. In the original minutes of the Politburo meetings, a note was made that the resolution on the appointment of Ryumin was adopted based on a note from Ignatiev, but the resolution itself, recorded by the secretary, did not contain any notes about the vote (RGASPI. Op. 163. D. 1602. L. 30). This is additional evidence that the issue was resolved single-handedly by Stalin.

Pihoya R. G. Soviet Union: History of Power. 1945–1991. M., 1998. P. 92; Stolyarov K. Executioners and victims. pp. 70–77; Petrov I. First Chairman of the KGB Ivan Serov. pp. 107–111,115-131.

RGASPI. F. 558. Op. I. D. 117.

Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks and the Council of Ministers of the USSR. 1945–1953. pp. 84–85. 148

System of collective leadership Management system under N.S. Khrushchev Management system under L.I. Brezhnev Read the page in the textbook and give a comparative analysis of the policies of L.I. Brezhnev and N.S. Khrushchev.

The rate of economic growth of the USSR in the years.

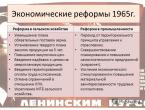

Economic reforms of 1965 Reform in agricultureReform in industry Reducing the plan for mandatory grain supplies. Establishing a firm product procurement plan for 5 years. Increase in purchasing prices. Introduction of surcharges to prices for above-plan products. Introduction of guaranteed wages for collective farmers. Cancellation of restrictions on private household plots. Strengthening MTB agriculture. Transition from the territorial principle of management to the sectoral one. Improving planning and increasing the independence of enterprises (cost accounting). Strengthening economic incentives and increasing the material interest of labor collectives.

Causes of difficulties in the economy Resistance of the bureaucratic Soviet system. Curtailment of economic methods. Lack of competition, shortage of goods. Irrational use of labor. Disparities in the economy. Exploitation of natural geographical factors.

Activities carried out by the USSR during the period of détente in international relations Measures to consolidate post-war borders Measures to strengthen security in Europe Measures to strengthen relations between the USSR and the USA Measures to limit nuclear weapons Read §35 and fill out the table.

Homework Read § Fill out the table “Activities carried out by the USSR during the period of détente in international relations.” Answer the question in writing 7 pages Prepare messages on the topics: - “Prague Spring 1968.” – The war in Afghanistan.

1970s - detente Reasons: There has been a deterioration in Soviet-Chinese relations. American-Chinese rapprochement is taking place. Military-strategic parity is being established between the USA and the USSR. Awareness of the pointlessness of increasing the number of weapons. Military expenses. Economic benefits from cooperation.

Bring into conformity 1. Final Act on SBSEA) 1968 2. Visit to Moscow of US President R. Nixon B) 1971 3. OSV - 2B) 1972 4. OSV – 1 and PROG) 1975 6. Treaty on the Prohibition of the Placement of Nuclear Weapons on the Bottom of Seas and Oceans D) 1979 7. Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

Bring into conformity 1. Final Act on the SSEG) 1975. 2. Visit to Moscow of US President R. Nixon B) 1972 3. OSV - 2D) 1979 4. OSV – 1 and PROV) 1972 5. Treaty on the Prohibition of the Placement of Nuclear Weapons on the Bottom of Seas and Oceans B) 1971 6. Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons A) 1968

Confrontation 1968 - USSR intervention in the internal affairs of Czechoslovakia. 1968 – large-scale assistance to the Arab countries of the Middle East in 1976. - the beginning of the deployment of Soviet RSDs in 1979 in Eastern Europe. - entry of Soviet troops into Afghanistan in 1983. – the beginning of the deployment of American RSDs in Europe. SOI program.

The Brezhnev Doctrine Justifies the USSR's intervention in the internal affairs of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe that were part of the socialist bloc. The concept appeared after Leonid Brezhnev's speech at the fifth congress of the Polish United Workers' Party in 1968.